In January of 2018, the first-year students at Bard’s Center for Environmental Policy (CEP) travelled to Oaxaca, Mexico to visit and learn from indigenous and local communities. We had an opportunity to talk about methods for environmental conservation as well as practices that make life easier (to that same end) living in high altitude or areas with low rainfall.

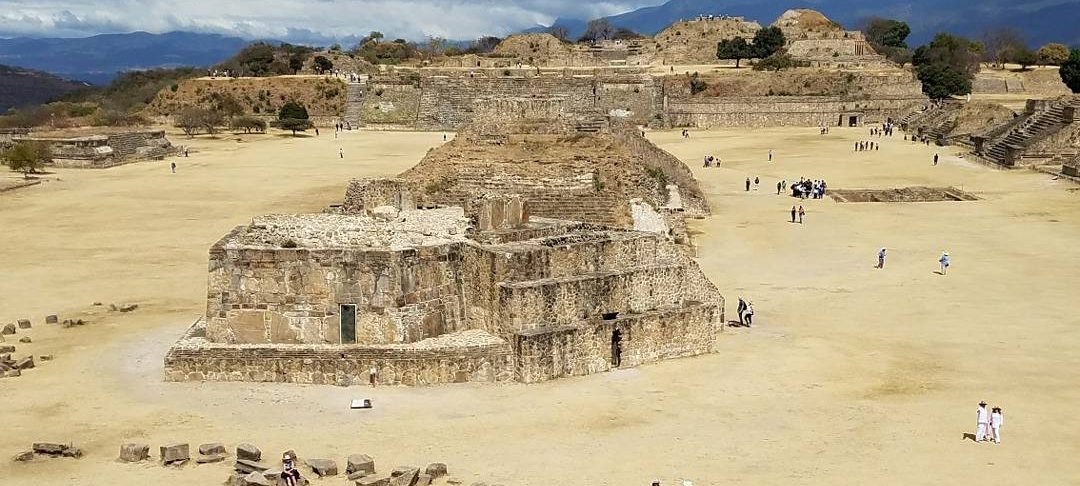

Toward the end of the trip we were also afforded some leisure time. Most of the class took the opportunity to visit Monte Alban, a pre-Columbian archeological site that was a Zapotec cultural center around 2000 years ago.

My curiosity began to bud as our guided tour started. The guide was effective and engaging and managed to give the tour in both English and Spanish simultaneously, an impressive feat. He  explained that the mountain upon which Monte Alban sits was leveled by the Zapotecs in order to build their city and that this process took 300 years to complete.

explained that the mountain upon which Monte Alban sits was leveled by the Zapotecs in order to build their city and that this process took 300 years to complete.

As we walked up to the top of the city, our guide revealed that the inhabitants of Monte Alban built reservoirs within their elevated city to capture and store rainwater for use. Having visited the water retention dams in Cieneguilla (designed to capture water from the 6-month rainy season in Oaxaca and store it for year-round use), this development was something I had expected to see. It was when our guide told us that these reservoirs were not constructed until 300 years after the city was completed that I began to be puzzled.

He explained that the original inhabitants carried water up from the valley below in ceramic pots. Having visited the nearby Cieneguilla and heard how the residents there moved down their watershed when their naturally formed lagoon broke during a particularly rainy season, I could not fathom a development project on that scale with water as an afterthought.

Later on the tour, I asked our guide if mud and pooling were issues to contend with during the rainy season. He assured me that when the city had been occupied, the vast flat expanses had been plastered over.

However, a problem with modern development i s the impermeability of paved surfaces, which redirect water instead of allowing it to flow through the ground and into the water table. If the mountaintop had been plastered, the inhabitants should have only seen water at the low point of the paved surface moving much faster than it would have had it been given the opportunity to infiltrate through the soil. Even today I am baffled.

s the impermeability of paved surfaces, which redirect water instead of allowing it to flow through the ground and into the water table. If the mountaintop had been plastered, the inhabitants should have only seen water at the low point of the paved surface moving much faster than it would have had it been given the opportunity to infiltrate through the soil. Even today I am baffled.

As we had some time to wander the site independently, I looked for environmental imprints of settlement, but there seemed to be no record of water capture systems, kitchen or food preparation sites, or excrement disposal. There was also no mention of any of these on the plaques available to tourists. Either the original residents of Monte Alban lived (and functioned) very differently from modern day Oaxacans, or the history is incomplete.

Either way, my next visit to Oaxaca will have to be after an immersive review of the current literature in Mesoamerican archeoanthropology.