Imagine that you’re walking through a park, breathing the fresh air. The soil right off the path is rich and healthy looking. You get to a water fountain, and you take a drink of the clean, refreshing water.

In 2019, we expect this type of scenario. We can safely breathe in the air, walk by the soil, and drink the water. But do we ever think about all the time, effort, and money that goes into keeping the air, soil, and water healthy for us?

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is entrusted by Congress with administrative powers to “protect human health and the environment”. Since its creation in 1970, the EPA has had the authority to carry out the logistics behind Congress’s environmental laws. This means that it’s responsible for ensuring that our air, water and soil are held to a safe standard, including inspecting and monitoring state level actions to ensure compliance with law.

However, Congress has historically not provided the EPA with the funding to fully execute these responsibilities.

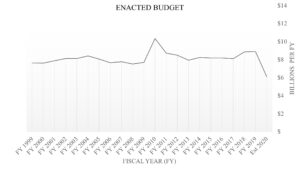

For the past two decades, appropriations have been relatively flat. With a 2010 stimulus funding exception, the dollar amount in each year’s enacted budget has remained unchanged.

Even worse, adjusting for inflation reveals a 24% decrease in appropriations for the EPA. In 1999, the EPA received about $7.6 billion (which is about $11.6 billion today). In 2019, it received about $8.8 billion – a decrease of 24%. And if approved, the Trump administration’s 2020 budget proposal will deepen the cut to 48% between 1999-2020. (See the EPA’s Budget and Spending, with adjustment for inflation from BLS.)

Plus, in the same two-decade timeframe, EPA has also experienced a 22% decrease in staff. In 1999, EPA employed over 18,000 workers, which has now shrunk to just over 14,000. It’s safe to say that a $2.8 billion cut in funding will continue the decline in staff.

So, what does all this mean?

- Lack of funds to allocate to state-level environment protection departments

- Fewer grants and funding opportunities for scientific research

- Limited capacity for regulating chemicals and assessing their risk

- Significant drops in inspections and audits to ensure compliance

And these challenges come at a time when EPA responsibilities are also becoming increasingly complex. Currently, about 125 million citizens are living in air quality detrimental to their health, and 18 million people are being served by pipes that violate EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule. The EPA’s list of contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) is growing continuously, with no timeline of when health implications will be determined.

Over 59% of the US population lives within three miles of sites in need of remediation, translating to 188 million Americans, with about 53 million living within three miles of a Superfund site. The number of Superfund megasite designations are growing, with price tags as high as $108 billion and completion dates scheduled decades from now.

How do these challenges play out on the ground? The implications of budget cuts and resource constraint challenges can be felt on the ground level, and in the case of Flint, Michigan, many of these challenges added fuel to the flame of the water crisis.

In 1974, Congress passed the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), and the EPA has worked with states to keep drinking water safe. But, starting in 2014, both the state and federal agencies failed in this responsibility to Flint. In the subsequent investigation of what happened, the EPA’s Office of Inspector General (IG) found that the EPA was not proactive due to “limited oversight resources.”

A review of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) (Michigan’s state agency to ensure compliance with the SDWA) found that “longstanding inadequate resources” contributed to a loss of staff and “significant loss in expertise and technical knowledge”. MDEQ was also found to be working with “data information systems…not sufficient to allow for adequate compliance tracking in addition to EPA-required reporting needs”.

A review of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) (Michigan’s state agency to ensure compliance with the SDWA) found that “longstanding inadequate resources” contributed to a loss of staff and “significant loss in expertise and technical knowledge”. MDEQ was also found to be working with “data information systems…not sufficient to allow for adequate compliance tracking in addition to EPA-required reporting needs”.

Reports from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), an independent research arm of Congress, provide insight into the workings of the EPA before the crisis began. They found that limited funding undercut the EPA’s ability to provide grants to states for inspections and audits of drinking water violations, and to work with state-level agencies to ensure complete and accurate data collection and management. Between 2007 and 2009, only 17 audits of state and regional level departments were conducted and zero were conducted in 2010.

Multiple reports flag concerns that resource constraints will continue to impact other areas of environmental protection on the state and federal level. For example, the proposed Trump budget cuts would directly impact the ability of the EPA to enforce the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act (Lautenberg Act). The 2016 passing of the Lautenberg Act provided the EPA with greater authority to regulate chemicals and responsibility to ensure that new chemicals do not mean unnecessary risks to human health before entering the market.

While there is a hefty price tag on funding the EPA, there is a significant return on investment.The economic costs of health impacts due to pollution are well documented, as is the savings with cutting pollution. There are also significant returns that comes with audits, inspections, and investigations, as conducted by the IG.

But nothing is as priceless as a walk through a beautiful park.