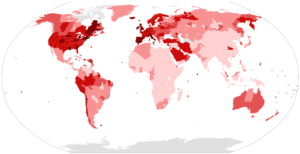

Covid-19, as it’s spread to every corner the globe and claimed more than 125,000 lives, has pushed aside almost every other major news item for the past three weeks. It’s forced dramatic shifts in our day-to-day behavior, and it’s drawn lines among demographics, proving itself to be more dangerous to the elderly, the immunocompromised, the uninsured, and those with low incomes in areas with serious air pollution.

Unemployment in the United States has risen to over 20% in the last two weeks—and that’s excluding hundreds of thousands who likely have not yet filed for unemployment benefits. Economist Betsy Stevenson argues that the unemployment rate might actually be much higher—reaching beyond the benchmark set by the Great Depression. While many are struggling to adjust to this new normal, there is every chance that the economic impact of the coronavirus will be far deeper than the 2008-2009 recession.

The consequences of pandemic quarantine definitely extend to the environmental realm. As decreased carbon and pollutant emissions from the slowing of economic activity lead to clearer skies worldwide, global strike movements like Fridays For Future (led by Greta Thunberg) and the Sunrise Movement are struggling to adapt their tactics to new, virtual platforms. The Trump administration has taken advantage of the national and international shift in focus to relax pollution regulations, suspend enforcement, and move forward with drilling in multiple national parks despite steep falls in the price of crude oil.

It is possible that a focus on economic recovery will, in the coming months or years, overshadow the climate emergency. Yet there might be a silver lining to that focus. The last time we experienced a recession this large, nearly 90 years ago, it took the New Deal and World War II to pull us out. The New Deal created safety net programs and economic recovery measures that set the scene for a dramatic shift in labor relations, and World War II required extremely high levels of military industrialization that permanently reshaped the American economy. Climate and policy experts have long suggested that we need a similar scale of transformation to seriously mitigate climate change, but many despaired at finding enough impetus to create such a transition in the short time frame we have been given.

Molding environmental policies into economic recovery plans could be that opportunity. According to Amy Hughes, senior manager at the Environmental Defense Fund, “there is a necessary restructuring and rebuilding of our economy ahead, and if you’re looking for the chance to insert solutions, the time is now.”

That transformation would not be an easy battle. Traditional economic recovery efforts support economically powerful actors with the end goal of reducing unemployment, stabilizing financial markets, and re-ramping up production. But a recession of this depth, with this level of unemployment and with our reliance on fractured and underfunded social safety nets, might provide us with the chance to engineer that process differently.

Environmental organizations have already begun to advocate for economic recovery proposals that decrease the carbon intensity of our economies, rework unsustainable agricultural and food systems, and enhance legal provisions of labor rights. Greenpeace, the International Energy Agency, and World Resources Institute have made calls for national governments to make stimulus packages contingent on modernizing energy systems—and multiple national governments are engaged in asking the IEA for advice on implementation of renewable energy policy into recovery plans. The Environmental Defense Fund may soon make a call for legislators to build low-emission agricultural practices into the US agricultural support bills that will roll out in a few months.

And in the coming months, we are likely to see more of these ideas for sustainable transformation emerge from different actors nationally and internationally—hopefully they are taken seriously.

In a surprising turn, market forces might be on the side of restructuring as well. It is possible that the coronavirus recession could kick the bucket for coal, accelerating mine closures and the retirement of costly, aging coal plants.

The American shale oil industry, standing on unsteady and billion dollar debt-ridden legs, might be outdone by the price drop in oil—shale oil only remains profitable when global prices come out at $45 per barrel, and projections for the next year range from $17-$35 per barrel.

Despite the federal government’s willingness to invest $20 billion in domestic oil during the crisis, as indicated by Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, debt-ridden domestic oil companies might lose their competitive edge.

Certainly, should the incoming administration decide to move forward with subsidizing large-scale renewable technology instead of propping up the dying fossil fuel industry, there could be serious improvement.

If the American citizen is presented with the proof that our country and world can seriously and dramatically reorganize its economic and political strategies in response to the coronavirus pandemic, we might be able to reshape the national understanding of what actions are possible to take in mitigating and adapting to climate change. We might also be able to do the highly necessary democratic work of reshaping and realizing a functional social contract.

In the post-coronavirus world, our dreams of deep structural, environmental change like that of the Green New Deal might have deeper roots. A fair amount of that depends on the federal political landscape in the coming months, the ability and willingness of municipalities and states to incorporate environmental policy into recovery plans, the curve that the economy takes in recovery, and the staying power of what might be temporary unemployment. As usual, we can only wait and watch it out—and, of course, organize.