You’re sitting in a classroom as a sophomore in college. You’ve recently moved from your rural, inland city to a coastal community bordering Malibu, California. At 19 years old, you feel you have a good understanding of what the world is like, and will be like, for you and your future family. Everything is set in stone—you have a vision, your dreams concrete and within reach.

But suddenly your vision is shaken to its core with the professor’s introduction of your next class module: anthropogenic climate change.

How can this be? How have you never even heard of climate change? Why did it take an entry level environmental science course in college for you to finally learn about the most important issue of your generation?

Your classmates shrug it off as if it were common knowledge, a household topic. As you watch your dreams sharply take the next exit, you’re overcome with anger and confusion.

Geographically unlucky?

This was me, fewer than five years ago.

I came to learn that where I grew up was a primary factor in my lack of environmental literacy and knowledge about climate change. This is because environmental literacy, rooted in exposure to environmental education, often develops as a product of place-based learning. In inland/rural regions, it’s harder to access traditional natural places and thus harder for students to get hands-on experience in the environment. In coastal regions, mountains, beaches, and parks are often more accessible.

To describe this gap in access to a critical resource—environmental education—I’ve coined the term “environmental education desert,” taken from the more commonly known term “food desert.” Environmental education deserts can be defined as geographic areas (often described using census tracts) where there is limited access to environmental education, both classroom- and place-based.

This idea is backed up by research. A 1991 study, for example, found that if a student lives in a geographic area that is farther from natural places, such as the coast or the mountains, they will likely have less experiences in these areas and may express lower levels of concern over the health of these environments.

In a California case study’s survey asking students how often they visit natural places, the average number of days per year for students living closer to the coast and mountains was 91.22 days compared to 32.64 days for students living in inland, rural areas that are further from traditional green spaces (unpublished data).

This led students living in inland, rural areas to display less concern about environmental issues and significantly less awareness of environmental terms than did students who lived on the coast (unpublished data), a factor of both green space access and political climate. Those inland areas were, to varying extents, environmental education deserts.

A new environmental justice issue

However, geography alone cannot explain the this disparity in environmental education access.

Other studies find that ethnic minorities experience far greater constraints in access to natural areas and are often culturally excluded from outdoor learning. They argue that stark disparities in environmental literacy exist between communities of color and white communities, largely attributable to the disproportionately high exposure to environmental risk and compromised availability of natural places among ethnic minorities who often reside in urban areas.

And geographic situation is not the only factor that influences environmental literacy. Schools in more conservative areas typically introduce fewer environmental topics and curricula than do schools in progressive areas, as public attitudes about climate change-related policies are strongly intertwined with political party affiliation and ideology.

These disparities in access are an environmental justice issue because children’s exposure to environmental education discriminates based on those factors.

Closing the gap: transforming deserts into oases

To transition environmental education deserts into “oases,” integrating environmental topics such as climate change into standardized curricula, such as the Common Core State Standards Initiative, may be the strongest approach. Implementing such a standard could minimize the influence of political partisanship on environmental education availability.

If all students across America are exposed to standard environmental knowledge, irrespective of their proximity to natural places, income, or race, environmental literacy and concern are potentially cultivated. Moreover, a study examining the effects of environmental education and exposure among various racial and income groups indicates the influence of classroom-based environmental education on enhanced academic performance, which could have positive implications for schools and youth in the United States.

Additionally, a global database of education deserts may help education policymakers appropriately target environmental programs to marginalized communities with little access to natural areas.

Looking ahead

As individuals, we can contribute to the creation of “environmental education oases” by encouraging our local schools—both primary and secondary—to adopt environmental education measures by:

- including environmental education in their curricula

- increasing inclusive place-based learning through at-school activities and field trips

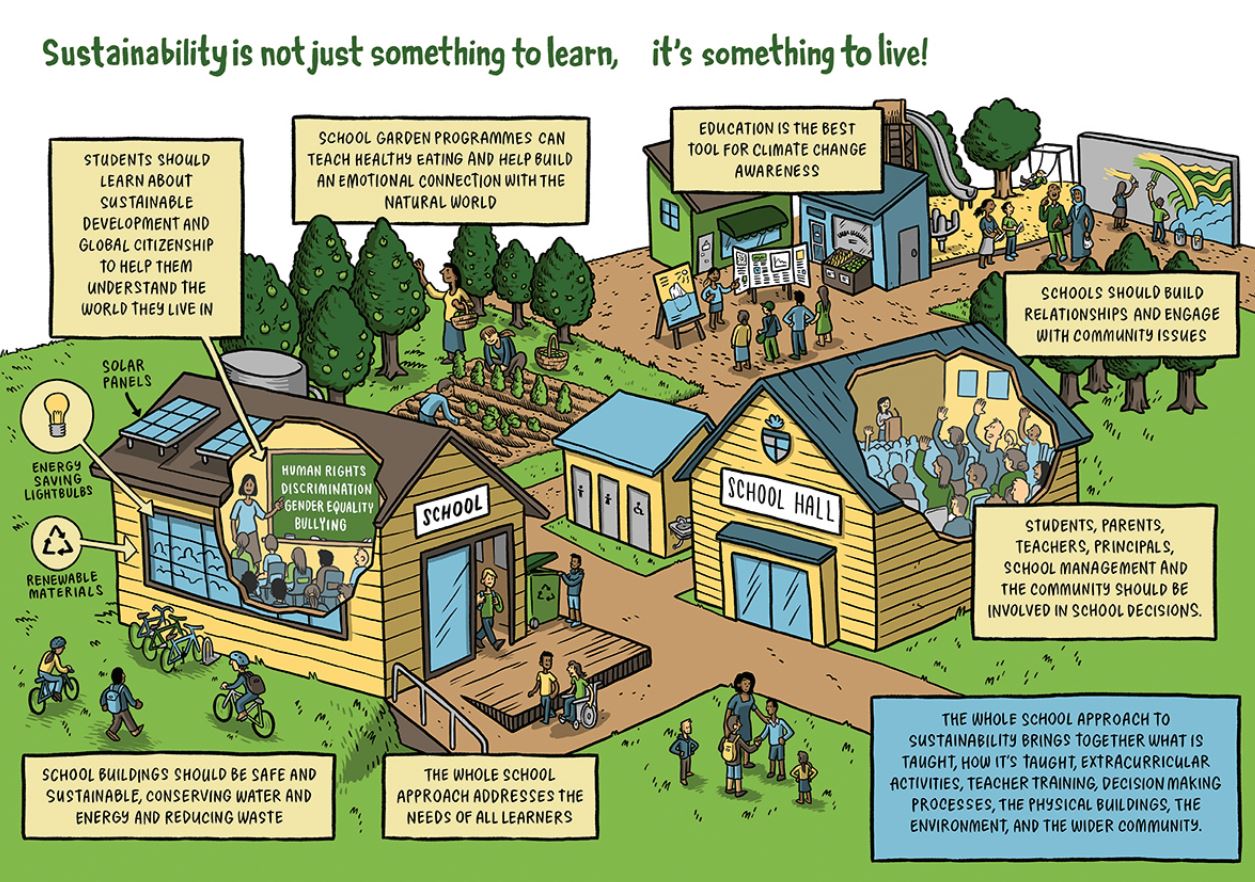

- adopting sustainability as a core principle of the institution, similar to the ‘whole school’ approach shown below

. . . in addition to living a culture of sustainability and teaching it within our own spaces.