We all produce waste, but where it goes next is often left out of the picture. For many, the path our waste takes after we discard it does not play a role in our daily lives. However, the massive amounts of waste we generate pose serious issues in terms of our capacity not only to collect it, but treat and dispose of it without causing human and environmental health risk.

Since waste management is so easily ignored, treatment infrastructure is neglected and unequal exposure to waste pollution is overlooked.

Our wastewater infrastructure is failing

Although this is not obvious to the public, current wastewater management infrastructure in the U.S. is severely lacking. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the maintenance and improvement of wastewater infrastructure requires a $271 billion investment over the next 25 years.

A large portion of this cost is due to electricity demands, as the systems that pump, process, and treat liquid waste are generally not energy efficient. The Department of Energy (DOE) estimates that municipal wastewater treatment plants across the country require an average of $2 billion each year in electricity costs alone.

Given that 95% of spending on wastewater infrastructure occurs at the local level, it can be difficult for small communities to prioritize waste management because of demands for other services. Who’d want to pay for enhanced wastewater treatment when that money could be put into a new park, or even a solar panel array?

Wastewater poses a disproportionate health threat

Without enough funding and technology to dispose of our wastewater safely, human and environmental health are at risk. This threat represents yet another aspect of our relationship with waste that’s hidden from our day-to-day lives.

Without enough treatment, wastewater discharge can degrade the health of water supplies, and in turn the safety of drinking water and recreation. One major cause of water contamination is through bacteria, as liquid waste contains pathogens that can lead to chronic and debilitating infections when consumed.

Those who bear the brunt of the burden that water pollution poses are often communities with the fewest resources. Low-income and non-white communities are often located next to waste treatment centers. As well, when waste-produced water quality issues arise in socioeconomically vulnerable areas, government led communication of health threat and effort to provide medical support frequently falls short.

Without the proper support by our government, waste-related water quality issues also reproduce conditions of poverty and injustice to limit broader awareness about those who are suffering due to waste pollution.

How can wastewater infrastructure be transformed to avoid health threats and even support marginalized communities?

We define waste as the things we don’t want: sludge, excess, bacteria, gross stuff—nothing useful.

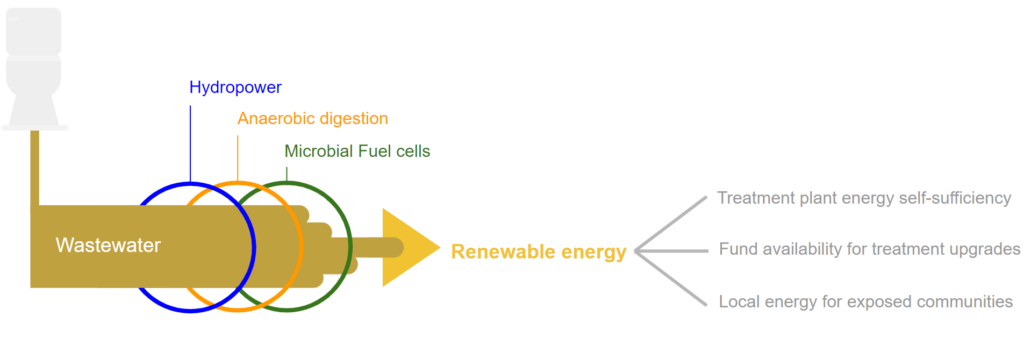

However, our waste still contains organic matter, and it can therefore be converted into energy. There are several ways to harness this secret energy:

1) Anaerobic digestion technology: solid waste and sludge from liquid waste are broken down and consumed by microbes in an oxygen-free (anaerobic) environment, which releases methane gas (CH4). This gas is captured and can be used to generate heat, electricity, or as a biofuel on its own.

2) Microbial Fuel Cells (MFCs): bacteria decompose wastewater in an anaerobic environment, but instead of producing CH4, they generate electrons through oxidation that are captured by electrodes within the cell. This technology works to directly generate electricity from wastewater, and can be used in a variety of applications aside from treatment centers, including septic tanks, wetlands, and aeration lagoons.

3) Hydropower turbines: through integration within wastewater infrastructure, hydrokinetic power can be generated to produce electricity through the flow of wastewater as it is processed through pipelines and tanks.

These waste-to-energy (WTE) systems offer an opportunity for wastewater treatment plants to capture renewable energy from waste, providing an onsite source of electricity. This can decrease costs, freeing up funding to improve the quality of water treatment.

As well, any excess renewable energy can be shared with local communities or sold to larger-scale energy utilities. For communities that are currently exposed to disproportionate health risk due to nearby wastewater treatment plants, WTE may be an opportunity to both:

- enhance treatment toward allowing for safe water resources and avoiding health threats

- provide a source of localized renewable energy

WTE systems are being used across the world, including in the US, Canada, China, Brazil, Argentina and Norway

In Vancouver, Canada, five of the city’s wastewater treatment plants use anaerobic digestion to produce heat and electricity through biogas, drastically reducing their energy demands. The municipality is also able to use energy from sewers to heat nearby buildings.

At the Hedong wastewater treatment plant in Urumqi, China, biogas from anaerobic digestion is used to cover 50% of the plant’s energy needs. In turn, this renewable energy source has reduced the plant’s CO2 emissions by 80%, allowing for a huge improvement to local air quality.

Xiangyang City, China also uses anaerobic digestion to generate bioenergy. One WTE plant produces enough natural gas to meet the daily energy requirements of 300 cars. The sale of the gas also produces more than $1.5 million for the plant each year. Due to the success of these systems in China, in 2017 the government selected 100 other cities to develop their own WTE strategies.

Using waste to produce renewable energy is an opportunity that cannot be disregarded

Integrating one or multiple WTE systems into wastewater treatment plants should be prioritized by local policymakers. By solving our complex avoidance dilemma, we can support energy efficiency, treatment quality, and environmental justice goals.

We must look past the unappealing nature of our waste to understand how valuable an energy resource it truly is.