Leggings and a fleece sweater may be the perfect quarantine outfit: cozy enough to compare to pajamas, but enough like real clothes that you feel proud of yourself for getting dressed. But did you know that every time you throw them on, a portion of them flies off to travel the world?  You may have heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch: the island of trash and plastic the size of Texas floating in the Pacific Ocean. The thing is, it’s not an island. Scientists characterize most of it as more of a plastic soup—and the main ingredient is tiny pieces of your clothing.

You may have heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch: the island of trash and plastic the size of Texas floating in the Pacific Ocean. The thing is, it’s not an island. Scientists characterize most of it as more of a plastic soup—and the main ingredient is tiny pieces of your clothing.

Not so fun fact: about 65% of our clothes these days are made of synthetic textiles, which is essentially a fancy way of saying they’re made of plastic. This is a big reason why clothing has become so cheap in the last couple decades.

When I say our clothes are cheap I mean both in price and quality, and these poor quality fabrics aren’t very good at keeping themselves together.

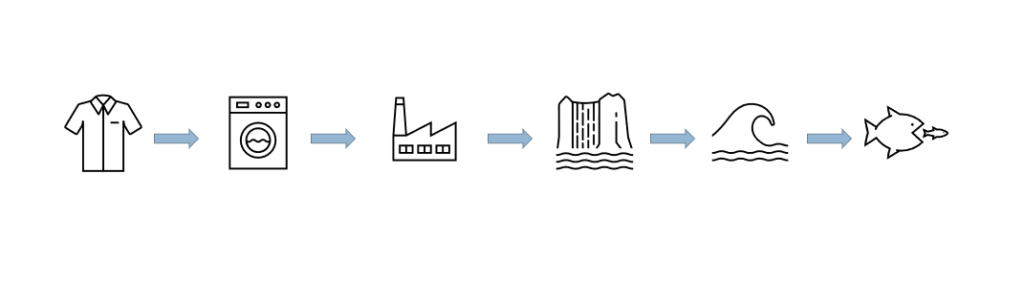

Every time you wash a standard load of laundry, the friction from the washing causes small fibers, called microfibers, to split off. Since many of our clothes are made of plastic, many microfibers are small bits of plastic. On average, a standard load of laundry releases between 640,000 to 1,500,000 microfibers.

These microfibers are so small that the filters used in wastewater treatment plants are no match for them. The tiny fibers go from our washing machines, to the sewer, past the wastewater treatment plants, and from there make their way into rivers, and eventually to the ocean, where they join the soup.

While it might seem like a manageable solution to scoop up an island of plastic, it’s much harder to imagine cleaning up the microscopic plastic seasoning of garbage patch soup.

Studies in the last decade have found environmental microplastics:

- From the sea-surface to the deepest parts of the ocean

- In Arctic sea ice

- In agricultural soils

- In freshwater lakes, rivers, and streams

- In the atmosphere

- In the bodies of over 558 different species of animals

- including fish, plankton, all species of sea turtles, 50% of all seabird species, and 66% of all marine mammal species

- And, most prominently covered by the media, in beer, salt, drinking water, various foods,

- and in human blood, breastmilk, and tissues

It’s estimated that on average we consume about a credit card worth of plastic each week, and by far the biggest source of these microplastics is fibers from synthetic textiles.

The main concern about microfiber ingestion is that plastics readily absorb persistent organic pollutants, such as PCBs, phthalates, BPA, and flame retardants. Even in small doses, these chemicals have human health impacts, namely hormone disruption.

Before you panic and swear off doing your laundry…

Consider that while some studies have shown that microplastics can have negative effects on living creatures in the lab, there’s still no conclusive evidence that this means they’ll significantly impact people or animals in the wild from ingestion alone.

Most of the lab studies that show direct harm use microplastic concentrations that are much higher than those typically found in the environment, and most of the studies are also done on invertebrates, such as shellfish.

*Keep in mind that this does not take into account indirect harms, such as ecosystem and economic stress.

But, before you shrug and throw that fleece in the wash . . . let’s think about the future.

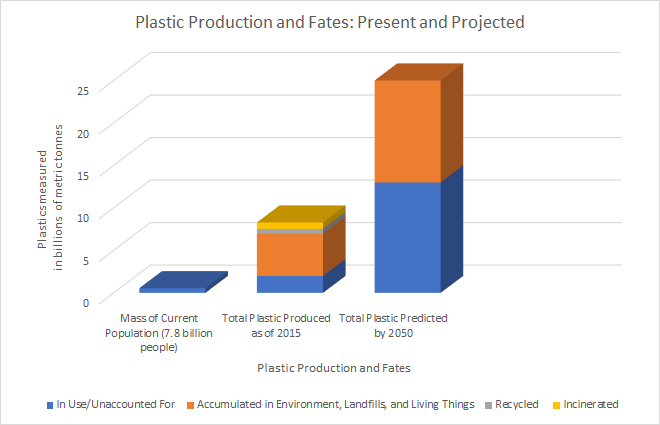

So far, we’ve created about 8.3 billion metric tonnes of plastic, a large portion of it since the 2000s—this is equivalent in weight to about 117 billion people, or about fifteen times the current global population.

Of this plastic:

- 9% has been recycled

- 12% incinerated

- and 79% has accumulated in landfills, the environment, and in living bodies.

If we continue at this rate, we’ll create an additional 5 billion tonnes of plastic and will have around 12 billion tons of plastic in the environment by 2050.

So, while the concentrations of microfibers currently in the environment aren’t currently enough to produce the negative effects shown in lab studies, we’ll likely see a massive increase in microplastic concentrations in the next few decades if we don’t make significant changes to how much we produce and how we use plastic.

Besides throwing out all of your clothes and becoming a nudist, or living in a sterile bubble, what can you do to get plastics off your back?

Primarily, we need to address this problem at the institutional level

We should pressure our representatives to pass regulations stemming the tide of microplastics at the source, the largest being microfibers from synthetic textiles. An example of effective legislation are extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes.

Currently the only national example of a textile EPR program is in France. In France’s version of this legislative package, producers are mandated to design and manufacture their products to meet certain sustainability principles. Producers also pay a fee, based on how much they manufacture, that goes into a pool of money to be used for “establishing the infrastructure for used textiles collection and recycling” and public sustainability education programs.

We should demand that the industries responsible for proliferating synthetic textiles become accountable for the whole life of their products. In the context of microfibers, this may mean avoiding non-biodegradable synthetic fabrics and designing fabrics so that they shed less and last longer.

But here’s what we can do as individuals

First of all, we can change our laundry habits to reduce microfiber shedding.

This includes:

- washing clothes only when they’re too dirty to spot treat

- filling the washer when we do use it

- washing with cold water

- using delicate settings

- adding fabric softener

- and hanging clothes to dry

Some of these habits also have the bonus perk of saving energy!

We can also try to capture a portion of microfibers from leaving our washing machines. This can be done by:

- installing a filter to catch microfibers from the washer’s outflow pipe

- or washing the laundry with these microfiber-catching bags or balls.

Most importantly, when buying new clothes, we can look for ones made of naturally derived fibers, such as bamboo, cotton, hemp, jute, linen, silk, Tencel or wool.

No material is without its own problems, so try to look for ones that are at least certified organic. “Sustain Your Style” has a good guide to which fabrics are good choices for the environment, and which ones to avoid.

Not only will we feel better about the environmental and health impact of our clothes, but our skin will be happy to be free of stifling plastic.

Trust me, ewe wool thank me.