Passed with a majority vote in both the State Senate and Assembly, Governor Cuomo signed the historic Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (The Climate Act) into law in July of 2019.

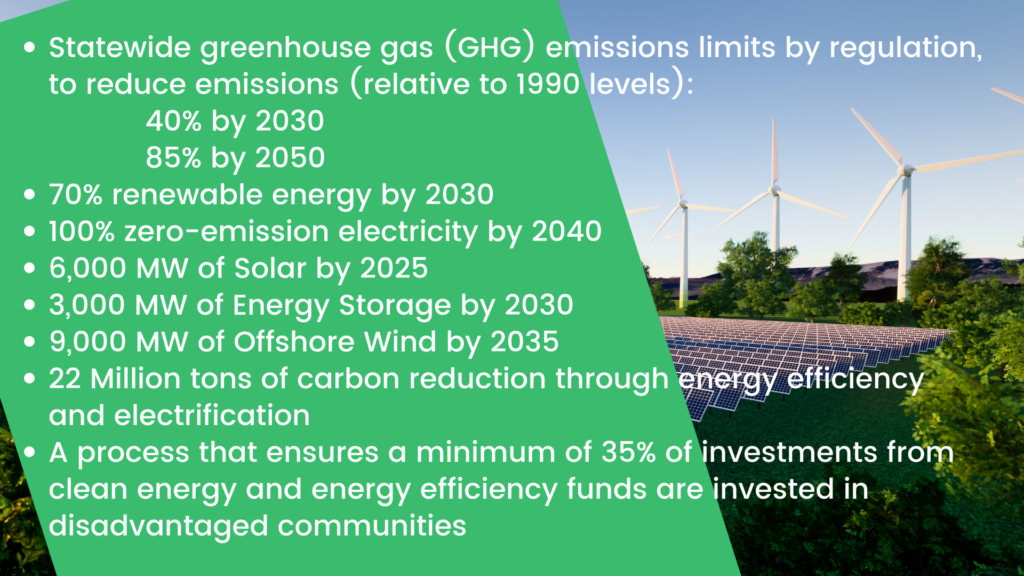

As perhaps our country’s most comprehensive and aggressive state-level response to the climate crisis, the Climate Act requires carbon emissions reductions from every sector, requiring the Department of Conservation (DEC) to establish:

Simply put, the Climate Act propels New York State down a path toward decarbonization by eliminating use of fossil fuels while centering environmental justice. The Climate Act stakeholder groups include Climate Justice Working Group, and an Environmental Justice Advisory Group.

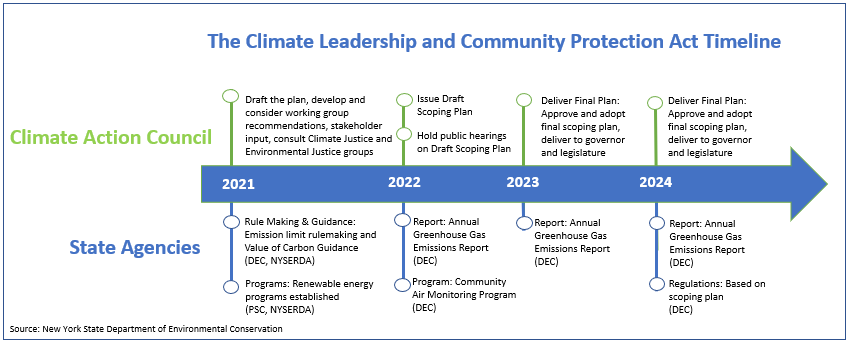

Additionally, a 22-member Climate Action Council, comprised of “state agencies and individuals with expertise in environmental issues, environmental justice, labor and regulated industries” is tasked with creating a scoping plan that will execute these considerably ambitious and rigorous goals. Draft scoping plans are currently being developed, with final plans and approvals set to take place between 2023-2024.

The Co-Chairs of this Council are New York State’s Energy and Research Administration (NYSERDA) President, Doreen Harris, and New York State’s DEC Commissioner, Basil Seggos. But ultimately, the DEC, under Commissioner Seggos, will be responsible for the execution and administration of the final regulations.

The Co-Chairs of this Council are New York State’s Energy and Research Administration (NYSERDA) President, Doreen Harris, and New York State’s DEC Commissioner, Basil Seggos. But ultimately, the DEC, under Commissioner Seggos, will be responsible for the execution and administration of the final regulations.

It’s a huge responsibility and one that requires strong leadership skills. I sat down to talk with Commissioner Seggos about his experience leading on precedent-setting climate legislation while balancing the DEC’s other focus areas, as well as leadership skills and lessons he’s learned along the way. Both my questions and his responses have been edited for brevity.

How does it feel to be administering perhaps the most admired piece of environmental legislation of any state in the United States?

Well, it’s a great honor. And I’m so thankful that we have this law here in New York. What makes me feel good is that we really didn’t know what we’d be doing when we got into it, but we’ve been able to find a path forward. When you talk about a law that requires you to reshape the entire economy, it’s going to take time to do it right.

“The New York Times called it the most ambitious climate law of any developed state or country in the world. So, to have that – all of a sudden – signed and entrusted to me as a leadership initiative was very humbling and exciting.”

You need to protect the economy. You need to protect all the individuals who are subject to the law, the businesses, the environmental justice communities. You need to provide a long-term pathway for the state to succeed knowing full well that there will be other states along for the ride with us. There are 25 states in the Climate Alliance which was founded in 1990. You can’t do these things alone. And if we put the state at a disadvantage, we drive jobs out of state, resulting in less revenue for us to do the work we need to do. So, it’s been humbling and exciting.

The confluence of factors right now is astounding and offers such optimism: think about the public support for federal action, multi-state action, the technology is almost there in many respects (at least on wind and solar), and of course, you have businesses—Fortune 500 companies—all moving in that direction at every level. So, it is a pretty awesome moment.

At the end of the day you can only go so far without broad public support. Where are you seeing that? And how do you plan to address it as regulations become clearer?

There’s a great deal of support for everything we’re doing right now. I mean, there are obviously sides to every issue. We’ll work through all of that. But we’ve got to deal with the regulated industries. We have to work with the unions. We have to deal with the problem of environmental justice in communities.

So what’s the strategy to communicate with them as to why this is important? We’ll have done enough work by that point to show them the way in which these regulations will actually improve their lives—not just the air they breathe, but also that we’re creating jobs in New York. If we reach a point where everything looks great on paper but the public is surprised by it or fearful of it, or that it could be subject to the political winds of opposition, that could be real trouble.

“And if we’re not embracing the fact that we need a significant long term public engagement strategy on this, then I think we are going to have a much more difficult time.”

So we really have to invest all that time up front and in the stakeholder groups, recognizing the reality of this will be very challenging. The communications plan that FDR put in place to help bring the American public along for the New Deal ride was a 10-20 year public relations strategy. It was kind of slow-moving editorial programs and political outreach. Now it’s social media and everything is instantaneous, like Twitter. I think the leash will be a lot tighter now than it might have been back in the 1930s and 40s.

Now for the fun part: If you were giving a commencement speech, how might you inspire the next generation of graduates?

Great question. I think about my kids who are still young. I think the toughest thing with them is to get them to embrace failure. I feel like society these days has a very low tolerance for failure and risk. I’d probably try to inspire the listeners with tales of failure and how you can use failure to ultimately succeed.

I think success rides on the coattails of a failure. I always say that as a parent. But also here in my position, we try a lot of things in government to help the livelihoods and lives of other people in New York. And if you’re not trying to build things, then I think you’re not giving yourself a chance to really succeed. I love getting up off the ground and trying again. It’s really a simple story.

Let me ask you about your career trajectory. Was this your plan?

I started out actually right out of college. I went to NRDC. I had interned there between junior and senior year. So I got to know a few of the folks in the New York City office. And then I crawled in on my hands and knees after graduation saying, “I’ll do anything, any single job.” And they gave me “any single job.” I was living with friends in a small apartment in NYC. And I would go into the office from three to six in the morning, working for very little, if anything.

But every single job led me to law school, which led me to the environmental litigation clinic where Bobby Kennedy was, and that led me to Riverkeeper. I then went to work for a private equity company for four years, and then came to the DEC when then Attorney General Andrew Cuomo took office as Governor.

So, you know, take advantage of the opportunities that are in front of you. I was fortunate to have opportunities, unlike a lot of folks, and I just didn’t want them to go to waste.

“I crawled in on my hands and knees after graduation saying I’ll do anything, any single job. And they gave me ‘any single job.'”

Now for four questions about the Climate Act’s successful execution:

(1) Emerging technologies. What happens if they don’t come to fruition?

Emerging technology is going to have to play a big role in whatever we do, but I’m not sure there’s one particular technology out there that we’re waiting to be developed. The pace of advancement on the microchip, solar panels, wind turbines, everything is becoming more efficient and more effective. The scale is significant. The prices are just dropping.

All of those things will be assessed against the new technologies like fusion energy, which people have been talking about for 40- 50 years. But we can’t rely on that. We can expect improvements to technologies we already have because of the amazing amount of money going into it right now, and all the money that the federal government is going to put into it in the next four years. We’ll be in really good shape on the technology front.

(2) How is the State going to pay for this?

That’s a huge question. We are mindful that this can’t get done without funding. We’ve put it to our own experts within government, as well as to advisors on the outside to help begin to develop funding schemes.

Some of the strategies being recommended already have funding strings attached to them. For example, transportation concepts that have gas tax ideas, or ratepayer fees on certain things. Some of these technologies will pay for themselves if the pricing is right.

Also, in terms of pricing, you have to think about the cost of not doing it. That to me is a powerful analysis.

“We see just our own $50 billion dollar impact over the next 10 years from storms in New York. If we’re not making these investments now and translating those investments into future revenue in dollars and jobs, then we as a state can’t see the value of the investment up front.”

So those are numbers we’re crunching right now.

(3) Has anything surprising come out of the recommendations so far?

Nothing has been really surprising, but perhaps that’s because we’re so close to this issue on a daily basis and we’re not done with the recommendations. We have three panels that are presenting in the coming weeks. So while there is nothing surprising, there’s also nothing that’s been left off the table thus far.

(4) What gives you the most hope with the CLCPA?

Its inclusion of disadvantaged communities. The world has woken up to the inequities that many Americans face. We drafted the CLCPA before all the police shootings and everything else that triggered this national awakening, so we’ve gotten a head start on some of that really important work.

If you have a law that mandates that 40% of the benefits are felt in the communities that have experienced the most impact, then you’re talking about something that can not only get us out of the climate change problem, but also out of the racial inequities problem at the same time. I can’t think of anyone who drives through the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, Albany or Buffalo who appreciates seeing people living next to pollution.

The human impact of all of that has been so extreme that we can’t ignore it. We have to change.

Will there be expectations that municipalities play a role? Will there be some type of goal set for municipalities or counties?

We have a nascent version of that right now with Climate Smart Communities with two different goals: one from NYSERDA and one from DEC. That’s been really effective so far. Some of the communities are merely stating their aspirations, but some are actually going farther and investing money to be fully certified.

I think that will all be put on a fast track once the CLCPA is truly rolling and we’re talking about spreading the workload—as well as the benefits—all across the state. There’s a huge role for local government in this.

Will there be more job opportunities at the DEC for recent graduates?

I certainly hope so. We’re always looking to bring in talent into DEC. We have a staff of a few thousand and many are getting to a point in their careers where they are retiring, so there’s a bit of a shift underway. It’s exciting to see some of the younger folks come in here now.

Inspiring words from someone who’s in the thick of New York’s environmental stewardship. Keep your eyes out for new developments regarding the CLCPA (https://climate.ny.gov/) and be sure to follow Basil Seggos on Twitter@basilseggos