I’m in a classroom giving a lesson on the ecology of the Hudson River. As I always do, I start the class by asking the students: “How many of you have been down to the River?” And as usual, only about half the students raise their hands.

I don’t probe them about why, but I wonder to myself: “Why is this? Why are all of these students living in the Hudson Valley, in the watershed of this famous river, yet not experiencing the wonders that go along with it?”

Our Disconnected River Community

The Hudson River is an incredible system, navigating through rugged terrain and mountainous falls from the peak of Lake Tear of the Clouds to the extensive estuarine output in New York City, with a watershed spanning five states.

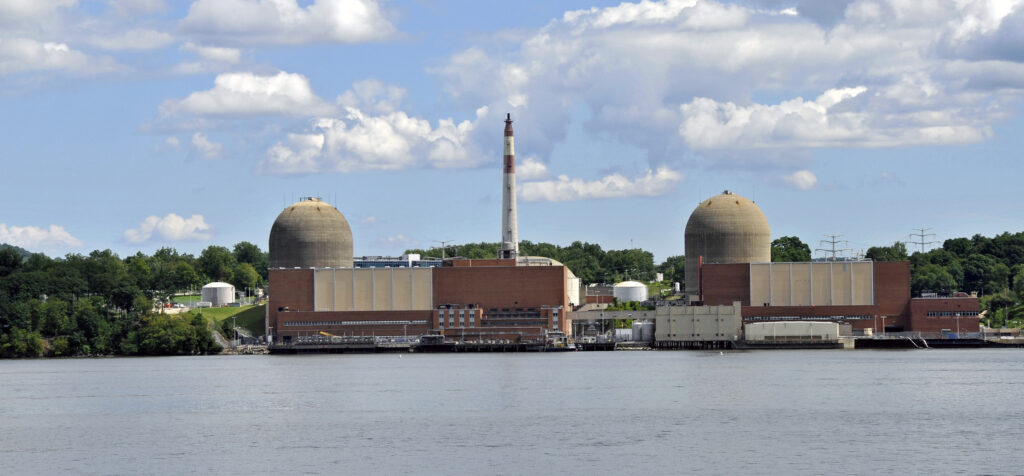

However, due to the follies of colonizing Europeans and industrial greed, access to the Hudson has been greatly diminished. Amtrak rails run along the entirety of the River’s Eastern shore, industrial systems take up substantial amounts of land, highways block access to shoreline recreation, and more.

The Hudson’s water quality is also a major issue. Hundreds of years of septic and industrial wastes have created less-than-ideal conditions. Though the past few decades have seen major improvements in water quality, the history of the River still tells people: “you can look, but you can’t touch”.

Finally, K-12 students in Hudson River communities, like the ones in my classroom that day, can be separated from the River by their school curriculum. Students learn Ecology through textbooks and exams that can be largely disconnected from their place.

So, what’s the solution?

Place Education on the Hudson River

Engaging students in place-based education about the Hudson can encourage them to be better caretakers and stewards of their environment and can help them realize their interconnections with the River.

I see two main ways for students to engage in studying the River: (1) through online curricula gathered and distributed by their instructors in a classroom setting, and (2) by engaging specialists who teach out of educational centers.

Online Resources

There are a good number of organizations that offer free online educational tools for instructors to use in their classroom. Instructors can find lesson plans through Teaching the Hudson Valley, NYSDEC Hudson River Estuary Program (HREP), Hudson River Park, and more. The Hudson River Foundation even has a guide to online resources, where they’ve compiled links to more Hudson River lesson plans than a teacher could ever get through.

But is this good enough? Can we compile these resources and expect students to become fully aware of their place? Or are we again saying, “You can look, but you can’t touch”?

In-Person Resources

Some Hudson organizations offer in-person programming that centers around the ecology of the River. For example, the HREP gives free half-day lessons, where students can get in the water, touch the animals, and make connections between water quality and the life that the river supports.

Similar to HREP, the Hudson River Field station, functioning out of the Columbia Climate School, gives free place-based lessons on the Hudson through field and lab work. The Hudson River Sloop, Hudson River Park, and The Hudson River Valley Institute also offer students the opportunity to learn on the River.

Limited Accessibility of River Education

While these in-person lessons are mostly free to visiting school groups, Hudson River schools, especially those that serve lower-income communities, still face challenges accessing them.

Funding for transportation is a major limiting factor. The HREP provides transportation funding through the Connect Kids grant initiative; however, this funding is solely reimbursement-based, meaning schools must still be able to pay for the transportation to qualify for reimbursement.

Funding on the organizations’ sides can also limit educational opportunities. The limited number of staff working out of these education centers may be spread thin, as these programs require work in outreach, coordination, preparation, and execution. Organizations may also often require gear and disposables for students to engage in their programming.

Creating a Connected River Community

Place-based education can give students scientific context, awareness of their environment, and foster appreciation for beings other than themselves. It can also give teachers a much-deserved break and a teaching experience outside of the norm. These programs are also a lot of fun and different than anything these students and teachers are experiencing day-to-day.

As is too often the case, it’s money that limits these educational programs. If we can decide that place-based education offers experiences rich in hands-on and applied science, then we can fight for a change at the institutional levels that control funding.

Parents and teachers should advocate for opportunities for their students to engage in place-based lessons about the Hudson River. Guardians can also improve their children’s sense of place by visiting any of the River access sites to create positive experiences in connection with the Hudson.

Looking back on your school experience, wouldn’t you have loved an excuse to get out of the classroom for a day, where you don’t have to read through a dense textbook or listen to a lecture? All students in the Hudson Valley deserve to be given chances to interact with the River, where they can look and touch.

I hope that in a few years, when I ask a class, “How many of you have been down to the River?” I see all of the students raise their hands.