In Marfa, Texas, prior to 2017, a house made of adobe bricks was appraised in the same way as any other house made of any other material.

Now, following an update by the county tax assessors, inhabitants of adobe structures pay 57% more in taxes than other homeowners.

Let’s back up for a moment. What is adobe?

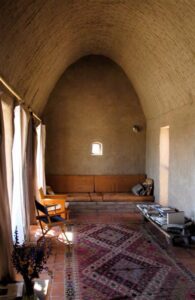

Adobe is the Spanish word for “brick,” and it’s the term for bricks made of clay-rich soil, straw, sand, and water. Traditionally, it’s the building material of southwestern Native American tribes such as the Hopi, Navajo, and Paiute. Techniques for building with this material extend from Egypt to the Mediterranean, and even to Ireland.

In hot, semi-arid climates, adobe works as a

capacitor year round, meaning that it stores heat within its walls. This keeps indoor temperatures relatively stable even in the extreme heat of summer and the cold of winter. Adobe therefore provides infrastructure alternatives to buildings that rely heavily on HVAC throughout the year, stressing the energy grid and threatening water supplies.

What’s the relationship between wealth and mud?

As concrete, steel, and glass became the norm in the US Southwest and architecture methods changed, a stigma attached to mud houses. It was one of class: if you lived in a mud house, you were probably among the poor.

Sandro Canovas, a skilled adobe artisan, instructor, and community member in Presidio County, Texas explains, “70% of the County is Mexican or Mexican-American. Some people like to call that indigenous population. The median income is between $19,000 and $24,000. It’s one of the poorest counties of the state, and probably the country.”

Some communities have retained the use of mud as a primary building material due to its accessibility and myriad benefits. In Presidio, however, adobe’s popularity with the area’s influx of wealthy newcomers has become a way to boost the county’s tax revenues.

So why, on the west side of Texas in a rural art town, are adobe houses so much more expensive?

In 2017, in order to follow through on its tax commitments to the state, Presidio County tax assessors opted to raise the property tax on adobe structures. The decision followed an increase in the number of people moving to the county and building large adobe houses. These new residents often had higher incomes than the residents already living in the county.

Not only had the newcomers gentrified the area, they had gentrified the most affordable building material available.

The majority of previously existing adobe houses were small, one-story homes passed down by families that had resided in Presidio county for generations. The increase in property taxes rendered many properties too expensive for their ancestral residents to maintain. This meant that residents living there either had to leave or put off necessary renovations to their houses. For some homeowners, it was less expensive to tear their adobe houses down and build concrete equivalents in their place.

What’s so wrong with concrete?

Unfortunately, concrete has higher environmental and economic costs than adobe, including:

- Capacitation (ability to hold heat)

- Toxicity

- Non-biodegradable

- High monetary cost

- Inaccessible to produce without machinery

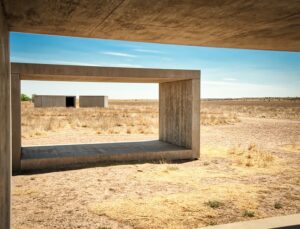

15 Untitled Concrete Works by Donald Judd. Judd’s concrete structures have stimulated a booming art-tourism economy in Marfa. Ironically, after the local tax increase on adobe, it’s become cheaper for some homeowners to replace their adobe homes with concrete bunkers not dissimilar to those created by Judd. Photo by SBMeaper1.

A life-cycle analysis of concrete, for example, finds that it requires more chemical inputs and emits more carbon dioxide than adobe. Concrete does not biodegrade without releasing toxicants into soil, landfills, and waterways, whereas adobe’s earthen materials can reintegrate into the environment. Adobe is also cheaper to make, although it requires a high level of skill to build correctly. Those who learn the craft can build without heavy machinery, meaning they can mix, build, and plaster alongside community members.

How can we solve the problem?

Simone Swan, the founder of the Adobe Alliance, says:

“Adobe will be increasingly more of a political issue: As building materials rise even higher in cost than in this first decade of the 21st century; as industrial materials’ toxicity is perceived, as their cost of transportation increases with the price of fuels; as the climatic comfort and salubriousness of adobe walls are discovered, more budget-conscious dwellers will be drawn to the material.”

Swan’s prediction has held true, especially the part about it being a “political issue.” Energy-efficient architecture (like adobe) is a hallmark of climate resilient communities, especially under increasing environmental pressure.

Accessible, low-cost adoption of adobe could provide municipalities with an opportunity to safeguard against rising temperatures and decreased precipitation.

But how can Presidio and other Southwestern counties incentivize adobe for climate resilience without disenfranchising low-income adobe residents? Including a building size limit in the tax code is one option. Mansion-like adobe homes would be taxed according to the new update, but smaller homes would be excluded. Tax credits are another option, like credits for green energy.

Non-governmental organizations have the power to advocate for such measures, but it will likely be up to networks of active community members, like Canovas, to ensure that these issues are continually discussed and reassessed.

If you’re concerned about energy-efficient architecture and affordable housing, explore the alternative housing efforts near you. There’s a wide variety of alternative building options beyond adobe. Earthships, Biodomes, Earth-covered homes, and others are just a few options. Searching for nearby housing cooperatives is a great way to start, and many offer other sustainability projects as well.

Hi, I have a house in Terlingua that needs some repair. Do you have any contacts you’d be willing to share?

Thanks,

Dana Price

Hi Dana, I do not have any personal contacts that I can put you in touch with. I do know that Sandro Canovas works nearby and may be able to help you further. If you are on instagram, his profile is @eladobero

Or if you are on facebook, his profile exists under Sandro Canovas. Hope this helps.