By Dr. Jennifer Phillips

Over the coming decades, climate change will challenge regional, national, and global economies. Some regions of the world will see agricultural productivity drop by 50% by 2080, while regions will experience increased productivity.

Source: Hugo Ahlenius/UNEP

Part of the adaptation process will be to build resilience into economies and landscapes, and the food sector in particular. The “local food” movement embodies this restructuring, but I argue that the lack of articulation of what features characterize a resilient and sustainable food system is holding back progress.

The desire to discuss how we might move forward in building resilience through agriculture was the motivation behind the March 31st panel at Simon’s Rock in Great Barrington, MA, the first in the Bard Center for Environmental Policy’s Eco Forum panel series. Entitled “Climate Change and the Economy: Building Resilience through Agriculture”, the panel brought together experts from a wide range of disciplines to discuss the challenges and benefits of building local food systems.

Does local imply sustainable?

A commonly quoted statistic is that the average meal in the United States has traveled between 1,500 – 2,500 miles from the farm to your plate, suggesting an enormous waste of fossil fuels used in transport. The implication? Local food has a lower greenhouse gas (GHG) footprint.

However, the New York Times cites research estimating that transport represents only about 3% of the GHG emissions associated with food production, although this amount may be increasing. The rest of the emissions comes from production, storage, and packaging. This highlights the need to address GHG emissions that stem from other aspects of the agricultural sector, and it also diminishes the benefits of local food from a strict climate change perspective. From a pure GHG accounting, shipping fresh apples from New Zealand to Europe might produce lower emissions than growing and refrigerating them in Europe. Growing lush tropical flowers in South America and then shipping them to New York for Valentine’s Day is probably less carbon-intensive than heating greenhouses during cold New York winters. Local doesn’t mean sustainable – or earth-friendly.

Another argument against the local food movement is that most of us do not want 10,000 hogs livingnext door to us – but we want to pay low prices for meat that can only be met through raising animals in concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs). It is a variation on the theme of the old NIMBY argument – as long as I can’t see the hogs (or cows or chickens), I will take advantage of the lower price.

The term “local food” is clear – but if we want local food to also be sustainable food – and food that actually meets the high ideals of the locavore movement, we need to introduce some nuance into the definition.

Refining the model

Perhaps it is time to refine the model, to clarify our own intensions and values regarding food systems, so that we are supporting a vision that gives us what we want.

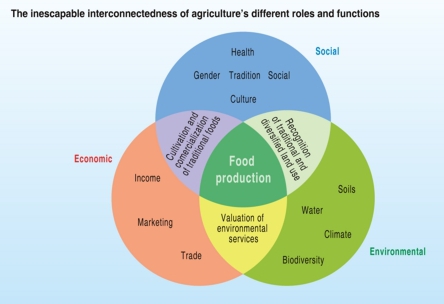

If we reframe the idea of “local” using Multifunctional Agriculture, a concept developed in Europe over the last decade and a half to help reform agricultural policy, we can begin to understand that agriculture provides more than just commodities.

The conventional paradigm says that the purpose of agriculture is to produce commodities – food, fiber and fuel. This paradigm leads to policies that ignore the attributes agriculture provides us with that have social, environmental, and economic value.

Using the MFA approach, we can identify some of the additional valuable attributes agriculture provides our communities with:

- Economic attributes: Commodities, Employment

- Environmental attributes: Water Quality, Biodiversity, Carbon Sinks

- Social and cultural attributes: Open space, Culturally-distinct landscapes, Recreation and hunting; Beauty

This framework for thinking about agriculture relates to the concept of “local” in that we usually value these attributes in our own communities – for example: jobs in our communities, water in our wells, and view sheds on our way to work. Eliminating agricultural systems from our local areas can also eliminate some of theses attributes from our daily lives.

Unfortunately though, not all types of agriculture actually provide these attributes. The trick is, how do we encourage farming systems that provide the goods and discourage the bads?

Market vs. non-market mechanisms to support the things we value

Most of these attributes are considered non-market goods – in other words, there is no way for society to express demand for them, so government usually needs to step in to make sure they are provided.

Since government doesn’t always achieve this, there are also non-governmental organizations that step in play this role, the most prominent being the land conservancies that protect farmland and help make it affordable for farmers to continue farming in the face of development pressure.

Finally, there are ways in which markets are starting to capture value from these “non-market” attributes prized by society, mainly through certification schemes that label food as “humanely raised”, organic, or “bird-friendly”. When consumers pay the premiums associated with these certification schemes, farmers receive the market feedback they need to go the extra mile in using sustainable management practices.

Challenges

No matter which methods are used to encourage farmers to supply the attributes we value in our local food systems, it requires that we know what we want and that we understand the system well enough to actually be able to achieve these goals.

So all of us – consumers, farmers, policy makers and agricultural scientists – need to learn a lot more about how complex social-agroecological systems work.

Nitrogen management is one example of a system that we need to improve our understanding of. In organic farming systems, farmers cannot use synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, which helps avoid the high carbon footprint of manufacturing that N-fertilizer. But managing nitrogen with cover crops and livestock manure can also produce greenhouse gas emissions and this organic nitrogen has the same adverse effects as synthetic nitrogen when it leaches into our waterways. Much more research is needed to optimize nutrient management to protect air and water resources.

Although there are many examples where high non-commodity attributes complement each other (e.g. the provision of high animal welfare, water quality and carbon storage in grazing livestock systems), there are examples of tradeoffs between attributes that we need to better understand.

Conclusion

We have only just begun to look at farming systems from an integrated holistic perspective and we can make a great deal of progress finding win-wins on the multiples goals we expect farming systems to achieve. But we need to refine what we want from our “local food” and start focusing on attributes we value about farming systems before we can direct policy and research toward achieving those goals.