A recent academic paper I read off-handedly mentions that trying to establish a collaborative water management group in California has a chance of success equivalent to a bunch of blindfolded people trying to find an elephant. After five months working for the Sierra Nevada Alliance. I optimistically disagree. Recently, there was much sobered centennial celebration of the LA aqueduct whose development was memorialized by Reisner’s Cadillac Desert. Even the most steadfast believer in the wealth of California’s water resources is beginning to realize that maybe we really are running out of water. However, water management and planning how to use this precious resource in a sustainable way is still a political issue and it’s most likely going to stay that way much to my charign. Navigating this complex, infuriating yet fascinating landscape is where my internships come in.

Decades of incredibly poor planning and political polarization over water have essentially established a gridlock in the state’s ability to adequately manage water by itself. This conflict has pit farmers against environmentalists, conservationists against those advocating against stewardship and has made everyone miss the big picture. Adovates from both sides bemoan the inadequacy of elected officials, shaking their fists and saying “darn Sacramento.” The reality is that the State is moving in the direction of empowering citizens and regional groups to manage their water resources and control the development of their respective cities and counties.

The Department of Water Resources has identified building the capacity of local governments to build their regional capacity to plan for and solve water related issues as a key objective in the most recent update of the California Water Plan. The way things are set up in terms of local governance is that there are state mandates as to how things should be set up and how environmental impacts should be disclosed but it’s up to the citizens to determine policy and enforce it. Citizens have the power to stall planning efforts, elect planning officials and to help craft general plans (a supreme document dictating land use decisions for 15-20 year planning horizons).

Initially, when I realized the power that citizens had over local planning processes, I felt eager to crush developers, make farmers pay the true cost of water and force people to notice the importance of the Sierra’s water resources. Yet, I rapidly learned the importance of tact. Given that citizens have so much power, either side (developers or conservationists) can bog down the planning process to the extent where nothing gets accomplished. Rather, it is important to build the capacity of citizens to understand their role in water management, to use their love of the Sierra as a tool to discuss and participate rather than litigate, and to help build the foundation necessary to procure funding from the state to manage our water.

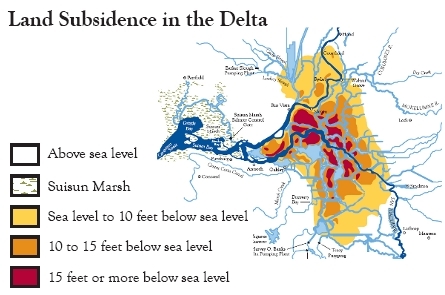

For example, citizens in a Central Valley county bordering the Sierra foothills helped pass an ordinance banning excessive groundwater use and export to neighboring counties in a massive victory against powerful agricultrual interests. Such an ordnance can begin to address issues such as land subsidence (below). This county is incredibly conservative politically but was able to combine environmental concerns with worries over theft of a property right (water) to pass an incredibly progressive ordinance at the county level. Naturally, this ordinance was immediately litigated by the agricultural industry but the citizens of the county have put up a unified front against it so we’ll see what happens.

Water has become such an ingrained part of our psyche in the Sierra. Having access to clean, useable and drinkable water is an entitlement. There is no convincing people otherwise in this state. Those who see it otherwise face a huge uphill battle in the policy arena. So, I began to think “why not use this to our advantage?” Local autonomy over water resouces could certainly be a way to bring both right and left to the table to figure out solutions to water management problems in our state.

Local autonomy over resource management can be an equally bad thing as well. While working at the Alliance, I realized that very quickly. The power of citizens as a policy tool is dependent on the willingness of a county to establish a strong platform for citzens to interact with planning staff, political ecology and the resources of the particular county. There is also a bad side to citizen engagement. Counties that have poor citizen turnout but excellent participation from developers can implement developer friendly policies that maintain the status quo of inadequately using water. Counties that have a conservative Board of Directors can dismiss citizen task forces that recommend policies that are “too progressive”. Clashes between citizens over planning issues that are not properly addressed by planning staff have also been known to last for periods upwards of 10 years.

There should of course be checks and balances as to how much autonomy local governments can have over their water and there currently are several imposed by the state. In certain areas, special districts hold authority over how counties can develop their general plans. Funding for water projects is also determined by state and federal entities. State and federal regulations require local governments to meet specific standards such as Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) and apply for Non Point-Source Discharge Elimination (NPDES) permits.

Citizen engagement is certainly both a malleable and imposing tool. It can be used for good or for evil in terms of water planning. Yet people who live in areas with sensitive natural resources should be given the chance to manage them. At the Alliance, I gained valuable understanding of how to facilitate and build the capacity of citizen action. I learned it is important to unify and speak tacitly rather than bellow and divide. I have a hell of a road ahead of me, but I am increasingly confident that citizen action will play a huge role in determining the outcome of California’s water resource management.