Emission allowances in Europe are too cheap to prompt greenhouse gas reductions, but don’t ask the US government what the price of climate pollution should be, lest they mention the Social Cost of Carbon

Originally posted on January 8, 2014 at theblisspoint.org

This is the third post in a series about the EU ETS

My previous piece about the European Union Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) makes clear that persistently low prices on climate pollution prevent the carbon market from working effectively. That is to say, an emission allowance price that won’t budge above 5 Euros per metric ton of carbon dioxide will not drive investment in carbon-free innovation. Without a hurried global transition to low-emitting energy systems, the future looks bleak — our climate will become increasingly unstable and extreme.1

Market price

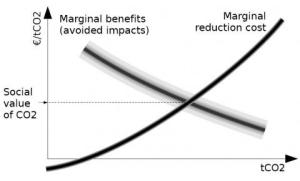

In a cap-and-trade system like the ETS, no central authority sets the price of greenhouse gas emissions. Instead the total number of allowances on the market sets a restrictive “carbon limit.”

Ideally, a scarcity of emission allowances would produce trades among emitting entities, with firms implementing the least costly emission-reduction strategies first. The price at which emitters trade allowances equals the cost of the last emission reduction necessary to meet the cap, according to economic theory.

So to drive up prices, the number of allowances must be reduced. In a closed system this lower cap would bring fewer emissions. The EU’s ‘backloading’ rescue plan employs this strategy by withholding carbon allowances until later in the decade.

Social Cost of Carbon

Nobody believes that €5 — or $6.80 U.S. — is the actual cost to society of one metric ton of carbon dioxide. But estimates of the true cost of greenhouse gas emissions vary widely.

Compare $6.80 to the latest revised estimates of the Obama Administration’s Interagency Working Group on the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) — $37 per incremental metric ton of carbon emissions.

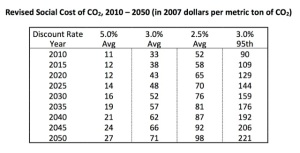

Note that $37 is simply the ‘cost of carbon’ that the group has chosen to publicize from the numerous results of an update to the SCC calculations. The SCC makes use of the averages of estimates from three integrated assessment models (IAMs) of climate projections, each run through five socio-economic reference scenarios.

The outcomes from the three IAMs are evaluated using three different discount rates, which are used to combine costs over time. The $37 estimate represents the average of all scenarios, discounted at 3 percent.2

I argue that the U.S. government’s calculation, though more than five times the price of carbon in Europe’s market, is still a very conservative estimate for four reasons.3

First, the chosen social discount rate is too high for assessing the costs of global climate change. For those familiar with discounting in a business setting, 3 percent may seem like a low rate — one that values the future highly at the expense of the present.4 But carbon dioxide emitted now will be causing atmospheric warming in fifty years; *social* costs and benefits that will affect the world far into the future are subject to a special *social* discount rate.

If you’re new to discount rates, you can think about them like an economist: costs that will be incurred further into the future carry less weight than immediate costs in today’s decisions (the same is true for future and present benefits). ‘Discounting’ future costs allows the SCC working group to unite today’s and tomorrow’s climate impacts into one Social Cost of Carbon.

But discounting can’t be applied equally to any analysis — the rate at which future costs and benefits are discounted matters. A high discount rate gives the future less influence over today’s evaluations, because future values are ‘discounted’ a lot. On the other end of the spectrum, discounting at zero percent makes present and future costs equally important in economic analyses.

Researchers analyzing expected future values get to simply choose a discount rate they deem appropriate and defend as such. The following example demonstrates why we must acknowledge the importance of choosing carefully.

A few years back, Sir Nicolas Stern, a top adviser to the British government, and Yale professor William Nordhaus engaged in a polite-yet-heated intellectual dispute on this subject. Simply by applying different discount rates, Stern and Nordhaus used largely the same scientific data to prove that a ton of carbon should be priced at $85 and less than $10, respectively.5

The trillion-dollar question remains unanswered: At what rate should we discount the anticipated costs of global weirding when we play this name-a-carbon-price game? Only economics nerds like Stern and Nordhaus debate such matters. And they can’t seem to agree.

One group’s opinion is certain, though: if future generations had a seat at the carbon-pricing table, they would advocate a rate much lower than 3 percent. Yet-to-be-born people certainly would not favor employing a discount rate so high that it treats people 24 years from now as if their lives are worth half as much as ours today.6

So 3 percent is too high — discounting the values of the future that quickly might lead us to destroy the planet in pursuit of riches that can’t buy back a stable climate. But we must discount at least a little to account for the fact that present gains can be invested in making the future better. Today’s profits from a fossil fuel-based economy could hypothetically fund the development of tomorrow’s clean-energy technology.

I am not qualified to have an opinion on the optimal social discount rate for evaluating the economic impacts of the climate crisis on our children and grandchildren, but we all know what’s at stake. The future of the planet can’t be assessed in the same way as a typical investment, even a typical investment in public goods or social welfare.

For intergenerational issues, even guidelines from the Obama Administration’s Office of Management and Budget promote using a discount rate less than 3 percent. I guess that department of the executive branch never spoke with the group developing the SCC.

To reiterate my first point, social discount rates, in order to treat future people equitably, must be low enough that they allow consequences that won’t show up until decades — even centuries — from now to shape our present evaluations and actions.

Second, the $37 Social Cost of Carbon completely ignores catastrophic climate risk. The distribution of climate change risk scenarios is not distributed in such a way that lends itself to looking at the average when establishing a Social Cost of Carbon.

The chance that global warming may produce cataclysmic effects — outcomes in which the standard of living to which we’ve become accustomed in the modern world is no longer achievable — make it hard to justify simply taxing greenhouse gas emissions based on the average climate change-socioeconomic scenario and then continuing our business-as-usual pursuit of profit maximization.

In technical terms, the worst-case effects of climate change would cause a great deal more damage than the economic models’ 50th percentile predictions. Statisticians call this phenomenon a long tail. In practice, the abnormal distribution of impact scenarios suggests that we should proceed with caution.

Even the Obama Administration’s report acknowledges the risks of the most extreme climate scenarios by including an extra SCC value, in addition to the average result at each of three chosen discount rates. This fourth calculation illustrates “higher-than-expected economic impacts from climate change further out in the tails of the … distribution.7

The fourth SCC figure is the models’ 95th percentile value, at 3 percent discounting. In May 2013, this estimate was $109 per metric ton — nearly three times the publicized “average” Social Cost of Carbon.8

This discrepancy illustrates the massive risk to which we expose our world and ourselves if we simply take the average of all projections when planning for the warmer future.9

The third reason that the Social Cost of Carbon estimate is too low has to do with the trend of all climate change estimates and projections — and the fact that reality has far outpaced most models. With each new Assessment Report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has become more certain about the anthropogenic causes of our warming planet, and the group’s projections for the future are increasingly ominous and confident.

This pattern of worse and worse forecasts from the leading international body for climate change study should not be ignored. Why shouldn’t we expect the prognoses to continue their descent into the realm of doomsday prophecies?

One reason that the future predictions keep getting more dismal is that models must be repeatedly updated to take into account climate change impacts arriving earlier than even the worst-case scenarios of earlier studies. Sea-level rise and the diminishing of Arctic sea ice extent are just two items in the list of climate consequences coming on more quickly than had been previously projected by the IPCC.

Studies that underestimate the degree of future change are often called “conservative,” but I argue that with respect to climate change, the conservative way to predict the future would be to plan for the most catastrophic scenario. The Obama Administration should raise their SCC to avoid making the same mistakes as the IPCC.10

Lastly, even the “conservative” IPCC, in their Fourth Assessment Report, remarks that the Social Cost of Carbon “very likely…underestimates” the damages of climate change. And the US EPA itself admits, “The models used to develop SCC estimates…do not currently include all of the important physical, ecological, and economic impacts of climate change recognized in the climate change literature.”

Limitations of data availability and model construction render impossible the task of aggregating all of the costs of climate pollution, even if emissions could be accurately measured and the future could be accurately predicted. Moreover, some of the costs of climate change are difficult to quantify. What is the present-value total cost of future ocean acidification?

In fact, the economics literature that informs the SCC often omits severe expected climate-change impacts simply because they do not lend themselves to monetization. Species extinction, for example, is not easy to economically value, and thus is left out of many climate economics models.

Because data is imperfect and models ignore many non-market anticipated costs, we should heed the Precautionary Principle. We should acknowledge that it is in our collective best interest to accept and apply a greater social cost of carbon than our complex models calculate.

The European Corollary

If the US estimate of carbon emissions’ external cost is not comprehensive enough, forward-looking enough, “trendy” enough, or vigilant enough — all of which skew the SCC figure toward inexpensiveness — then the almost-negligible price of an allowance in the European carbon trade must be far too low. Yet the ETS is a cap-and-trade system rather than an emission tax; nobody directly sets the price of carbon.

Do low prices mean that the cap-and-trade system failed? Or that it is working so well that emission allowances have become nearly worthless simply because total emissions stay under the “cap” more cheaply than expected? Most economists would respond in the same way they answer most tough questions: “It depends.”

It depends how the goals of the ETS are defined. It depends whom you ask. It depends on whether or not you believe in putting a price on pollution. It always depends on the discount rate.

President Truman once requested a “one-handed economist” because he was sick of hearing, “On the one hand, … On other hand, …” Well, this series of blog posts about the EU ETS may end up looking as if it were written by the Indian deity Durga — there will be a piece about every viewpoint.

The following addendum provides a glimpse into a once-prevalent perspective that has been regaining momentum recently: that the cost of ecological destruction cannot be expressed in dollars and cents. Certainly this argument deserves its own long-winded post; the next section is only a preview.

Non-monetizable harm

Evidently, using money as a metric assumes that anything can be traded for anything else. The idea that every cost and benefit in the world can be ‘dollarized’ provokes doubts from many non-economists (and from some scholars within the economics community).

Hard-to-quantify losses, like the aforementioned extinction, lead to an important dilemma. Assigning a dollar value to the survival of polar bears as a species suggests that for this amount of money society could be compensated for the end of that animal’s existence. Such a human-centric view offends people who think of the world from an ecological perspective.

On the other hand, if we exclude unmonetized damages from the societal cost of carbon — or exile them to the oft-ignored ‘caveat’ and verbal qualification appendices — then these costs are treated as effectively insignificant. In a capitalist world-economy, ‘priceless’ sounds a heck-of-a-lot like ‘worthless.’

Read more Bard Eco Reader blog articles about the Social Cost of Carbon:

Discounting the SCC: “Wait, this isn’t a sale!”

The SCC: the most important number almost no one has ever heard of.

1. For a basic explanation of the ETS and its current predicament, check out my blog post “Band-Aid for a Broken Market.”↩

2. The Interagency Working Group ran each climate and socio-economic scenario combination with 2, 3, and 5 percent discounting.↩

3. “Conservative estimate,” in this case, means “way too low.” But remember that America is still the Land of the Free (right to pollute the climate) — the Social Cost of Carbon is, at this point, an intellectual exercise.↩

4.[In the world of business, discount rates typically mirror the cost of capital or expected return on an investment of similar risk profile. For example, if I can invest my money somewhere guaranteed grow 5 percent yearly, then the future income generated by any other potential investment should be discounted at 5 percent per year, since I could just put all my money into the guaranteed-5-percent fund.↩

5. What’s more, they each had very convincing arguments defending their choice of discount rate. One sentence simplified summaries follow: Nordhaus, rather than deciding upon a rate at which we “should” discount future costs and benefits, used market interest rates to determine peoples’ actual time preferences. Stern, on the other hand, considers discounting with respect to climate change a moral issue, making a case that we should take intergenerational equity and sustainable development into account when examining alternate trajectories that diverge vastly and are highly uncertain.↩

6. According to the superscientific Rule of 72.↩

7. Interagency Working Group on Social Cost of Carbon. (2013). Technical Update of the Social Cost of Carbon for Regulatory Impact Analysis. United States Government. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/inforeg/social_cost_of_carbon_for_ria_2013_update.pdf↩

8. Before the November 2013 revision, the official SCC was $38. Again, this number was based on the average of every ‘run’ of the models. The results were discounted at 3 percent.↩

9. For reference, a few sources (one more) calculate that every dollar-per-metric ton increase in the price of carbon dioxide emissions will result in a one cent-per-gallon hike in gasoline prices. According to that hypothesis, a carbon tax of $109 would add just over a dollar to the price of a gallon of gas, while pricing emissions at the level suggested by the Obama Administration’s SCC would raise gas prices by a third as much. That the U.S. Social Cost of Carbon estimate would have such a small effect on consumer prices plainly illustrates how absurdly cheap carbon is in the EU’s cap-and-trade system.↩

10. And of course the Social Cost of Carbon should be implemented as something more than a theoretical exercise.↩