Getting Milk?

I don’t cry over spilled milk, but I’m not ashamed to admit that trying to navigating my way to the milk isle during peak shopping hours brings me awfully close to tears. Especially right before a snowstorm.

It’s not an ordeal I take up willingly, but today we are out of milk, so into the store I go. Somewhere between the cheeses and the yogurts, I bump into an old acquaintance.

“Hey man, it’s been a while,” I say.

“Yeah it has – what are you up to these days?”

“Well, I’m getting a masters’ degree in environmental policy from Bard College.”

“Oh. How are you handling it? I mean, since environmentalist types care more about the nature than people.”

It’s disheartening how many times I have actually heard some version of this statement, as if we humans are somehow not a part of nature, or that our lives and wellbeing are not interlinked with natural processes. The yogurts and cheeses aren’t there by magic, after all.

Of course, nature is complex, and humans influence nature in countless ways. More often than not, understanding the complexities of natural relationships and the human role in these relationships is more difficult than making your way to the milk isle during peak shopping hours before a snowstorm.

And yet, cultivating a certain level of public understanding regarding natural systems is a necessary component of effective environmental policy. After all, public policy, environmental or otherwise, is developed in a political context, and politics in a democratic republic like ours is influenced by public consciousness (and this brings up a thick slurry of other important issues).

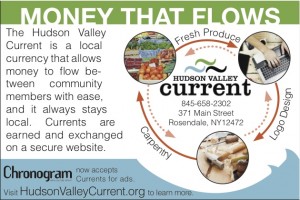

I reflect upon this in light of my own work for the Hudson Valley Current, a mutual credit system that I’ve worked for as part of Bard Center for Environmental Policy’s graduate internship program. After all, once I tell my grocery store acquaintance about this work, he is bound to ask me, right there in the dairy isle, “What does that have to do with environmental policy?”

At first glance, one might think there is no connection, at least not directly. But, to paraphrase John Muir, just dig a little, and you’ll find that everything is connected to everything else.

Building Sustainable Patterns of Exchange

The Current allows local independent businesses and self-employed individuals to exchange goods and services through an online software system that credits a user account when a good or service is provided and debits a user account when a good or service is received.

Because users are generally allowed to spend their credits below “zero” until they reach a standard debit limit, the Current system effectively allows users to create interest free lines of micro-credit as needed. Credits represent a tangible good or service and debits are repaid simply by earning credits, that is, by providing goods or services through the Current network.

There are hundreds of local credit systems throughout the world. Some are established particularly for environmental reasons. In parts of Belgium, for example, residents receive credits from their local government in exchange for environmentally beneficial activities such as composting programs or reducing household energy consumption. Credits earned in these systems are redeemable for certain municipal services like public transportation.

Other credit systems, like the Hudson Valley Current, aren’t specifically designed for an environmental purpose, but many mutual credit advocates believe that these systems provide general environmental benefits by changing patterns of economic exchange. For example, by supporting localized supply chains, local mutual credit systems are thought to limit harmful environmental impacts by reducing the amount transportation-related fuel use and emissions.

However, things can get complicated pretty quickly. Consider that eating an apple from Chile in late spring (which would be autumn to our southern hemisphere friends) could very well represent less green-house gas emissions than purchasing a New England apple, after comparing the energy efficiency of water transport to the energy intensity of refrigeration needed to preserve the New England apple. Of course, getting a local apple from your farmers’ market in October would almost certainly be less energy intensive than an apple from Chile any time of the year.

The point is, localization alone is not necessarily better for the environment. One has to consider how something is produced at least as much as where it is produced. This includes looking at energy and chemical inputs and how they affect surrounding areas. At the same time, there are indeed economic and social benefits that can be gained from supporting localized patterns of exchange. And, if local farmers are committed to using environmentally responsible methods (as many in the Hudson Valley are), finding ways to support these farmers is critical.

This is where we begin to find one thing connected to the other. One way the Hudson Valley Current can be used by farmers and other local business interested in sustaining our region’s environmental resources is to strengthen their position in local markets. To continue with the example of your local farmer, whether paying for advertising, farmer market fees, or materials to develop on-farm market infrastructure, the Current can be a source of community-based capital.

But Can I Buy Milk with That?

In one sense, the Current is not much different than old-school bartering. In exchange for building materials, a farmer can provide a CSA share. But by assigning credits and debits to each trade through the online platform, the farmer and materials supplier don’t have to make a direct trade. The materials supplier might not need a CSA share, but she can spend her credits on something else, like bookkeeping; the bookkeeper could, in turn, spend his credits on the CSA share.

Maybe we could think of all money in this way – as a kind of extended barter. Experimental projects like the Hudson Valley Current, however, seek to embed exchange and value within a given region. This is not at all to say that goods and wealth should be stuck in one place and never exchanged between different regions and countries. It is to say, however, that something can be gained by developing institutions that allow community members to create wealth and to see where that wealth goes, and perhaps more importantly, to see how that wealth is used and the impacts that it has.

At this early stage of development, the Hudson Valley Current is providing a platform for local independent businesses. But one day, perhaps individuals like me will be able to participate in this system of community wealth and use the Hudson Valley Current to get milk before a snowstorm.