By C2C Fellow Dana Drugmand

Originally published online at The Berkshire Edge on December 13

Washington, Mass. – This past Monday (December 8) Kinder Morgan, the firm behind the proposed multi-billion dollar Northeast Energy Direct natural gas line, updated its pre-filing application with the Federal Energy Regulatory Committee to reflect a new preferred route alongside existing power lines in western Massachusetts. The high pressure pipeline would convey natural gas from the fracking fields of the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania to eastern New England and its seaports. The pipeline would still pass through the Berkshires before running north into southern New Hampshire and dropping back down into Dracut, Mass.

According to the nation’s largest energy pipeline company, the route shift came in response to public outcry and staunch community resistance to the project. The new route avoids some environmentally sensitive areas protected under Article 97 of the state constitution and reduces the number of landowners in the direct path. But the company itself acknowledges that it expects continued opposition and that the pipeline continues to impact towns that have resisted, as well as some new towns that now find themselves in the line of fire.

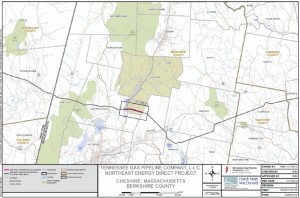

The new route enters Berkshire County in the town of Hancock from Stephentown, N.Y., (rather than into Richmond) and then continues east through Lanesborough, the southern portions of Cheshire, Dalton, Hinsdale, the northwest corner of Peru and finally Windsor before moving onto Plainfield and Ashfield in Hampshire County. This route avoids the sensitive habitats in Lenox that would have been disturbed had the route been carved out further south.

Despite several Berkshire towns such as Richmond, Lenox and Pittsfield being spared in the route shift, other communities like Dalton and Hinsdale remain in the path and towns like Lanesborough and Cheshire suddenly find themselves impacted. The new route crosses the Cheshire Reservoir and the Ashuwillticook Rail Trail.

The new, “improved” path also brings a compressor station into the Berkshires, with one now sited for Windsor. Originally, the preferred route had planned for a compressor station in Deerfield, a community that has taken an adamant stance against the pipeline.

As Rosemary Wessel of No Fracked Gas in Mass pointed out Monday night during a presentation in the town of Washington (one of the towns along the original route), compressor stations frequently blow off raw natural gas into the atmosphere. That gas not only contains some fracking chemicals, but it is released as methane, a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. Blow-off of raw gas also occurs at other points along the pipeline, including at maintenance (pigging) facilities and valve stations.

Wessel went on to describe other health and safety concerns associated with this kind of high pressure, fracked gas pipeline. But the main point she drew is this–the route alteration fails to address the primary contention of the opposition, which is that overbuilding natural gas capacity is unnecessary and unjustified.

Although the industry claims the region faces an “intensifying shortage of natural gas,” natural gas already fuels more than 60 percent of our electricity generation. Increasing energy efficiency leads to lower demand, Wessel said.

As Wessel pointed out, regulators’ own studies indicate that given current state efficiency programs, more pipeline capacity is not needed. The peak demand scenarios that are often referred to as justifying increased capacity are irregular and infrequent, and can be addressed through means other than a new pipeline.

One of those alternatives includes changing a policy that would reinstate an incentive for distribution companies to prepare for peak demands by storing additional (liquefied) gas. As Wessel explained, “[ISO New England] will normally pay back electric generators for excess gas that they stored and didn’t end up using, thereby reducing some of the risk of financial loss from overstocking. They took away that incentive program, and in their own memo said they don’t want to send the wrong signal about the relative scarcity of gas, they didn’t want the price of gas and electricity to drop because of that program, and so they discontinued that program last year.”

In other words, current higher electric prices are making it seem as though additional gas capacity is needed, when in fact ISO New England is failing to take into account alternatives like liquefied natural gas (LNG) storage, increasing efficiency, distributed generation and utility-scale renewables, including 1,600 MW of solar and 2,000 MW of wind that are mandated to go online by 2020. And while we invest in and build up clean energy sources like solar and wind, we could be upgrading and making use of existing gas infrastructure to meet peak needs.

The argument that the pipeline will lower gas prices is also questionable. The gas market is subject to price fluctuations, investments are risky and may decline, and especially given the increasing public opposition to fracking operations, the supply is not guaranteed.

Furthermore, the push for expanding the renewable energy economy further weakens the claim that more gas is needed. As Wessel explained, clean energy is the fastest growing part of the Massachusetts economy, providing 88,000 jobs thus far. If the low estimate cost of the pipeline were directed towards investment in clean energy, it could generate approximately 24,000 permanent jobs compared to the 3,000 temporary jobs the pipeline construction would bring. “Adding more gas to our energy mix only delays development of more sustainable energy solutions,” she said.

Besides obstructing the clean energy pathway and pushing us further down the unsustainable fossil fuel road, this pipeline would bring in much more gas than local residents could even make use of. The original call for added gas capacity put forth by the New England governors and ISO New England was for 0.6 billion cubic feet of gas. The NED pipeline would transmit 2.2 billion cubic feet of gas, raising speculation that much of the excess supply could be exported overseas, where the gas market is more profitable.

Kinder Morgan says it has 0.5 billion cubic feet of gas secured in local contracts and that it currently has no liquefied natural gas (LNG) export customers. However, the possibility and the pathway for export still exist. As Kinder Morgan’s Allen Fore explained in Dec. 8 interview with WBUR Radio Boston, a term paper writer, “We are an open access line. All natural gas interstate pipelines are. So if a creditworthy company comes along in the future, we have to be open to that concept.”

Given the potential for gas export on top of the other arguments against the pipeline, shifting the route makes no difference to those who remain firmly opposed to the project. “The principles haven’t changed,” explained Arnold Piacentini of Richmond. “We don’t need it. It’s bad for climate change, it’s bad for the environment, and so we’re going to keep fighting it. The fact that the route wiggled doesn’t make any difference in [people’s] attitude. So most people are sticking to principles, and I think that’s the way to do it.”