By Timothy Markle, M.S. in Climate Science and Policy 2016

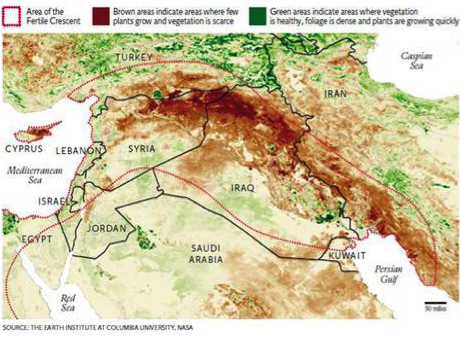

Each winter, the winds around the Mediterranean Sea shift and blow onshore. As a result, quenching seasonal rains fall on a land that receives less than 10 inches per year. The water collects and fills the rivers, streams, and natural reservoirs nestled in the hills of northern Syria. This is the site of the Fertile Crescent, home to Mesopotamia and the beginnings of human civilization.

In the winter of 2005-2006, however, the wind shift and accompanying rains never materialized. For Syria, it was the start of a five-year long drought that plagued its agriculturally rich lands in the north—the most devastating drought in Syria’s history.

What makes this drought particularly noteworthy is that it directly preceded the outbreak of civil war and that it has now been linked to climate change.

Linking conflict in Syria to climate change has rekindled this decades-long debate over conflict and resource scarcity. Recently, a study by Collin Kelley published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that “this is maybe the first example of connecting emerging climate change to a modern conflict,” and that a drought this severe was, “two to three times more likely” due to climate change. Indeed, this study supports a growing literature by NGOs, state governments, and the UN linking severe heat and drought with an increase in conflict.

But does climate change cause conflict? Kelley is quick to place caveats on any causal link, stating that climate change is only a “contributing factor”. Similarly, the Pentagon identifies climate change as a “threat multiplier” that imposes “additional risks” to affected regions. The idea is that climate change acts as a catalyst for conflict in the presence of other drivers. In Syria, these drivers are poor resource management, drought, and population pressures.

Using water to grow the economy

In the 1970s, then Syrian President Mazir al-Assad reformed agricultural policies to increase GDP and limit reliance on food imports. Farmers responded by planting wheat and cotton, two financially sound but water-intensive crops. Cotton harvests grew the national economy, and wheat production grew so rapidly that imports were halted in 1995.

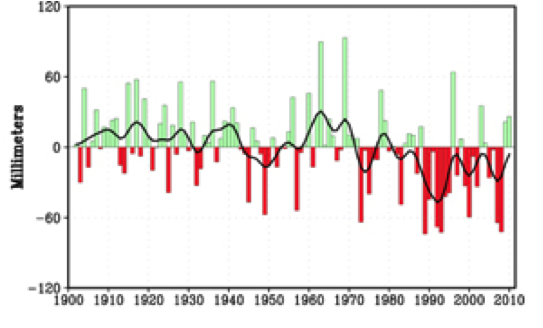

Agricultural success, however, came at the cost of water. Farmers were drawing water out of streams and aquifers at a pace faster than Mother Nature could supply with the seasonal rains. Sporadic, year-long droughts throughout the 1980s and 1990s limited natural recharge. This increased farmer dependence on wells to reach underground water supplies.

The result? Nobody was prepared for the drought in 2005. As conditions worsened, farmers dug newer, deeper wells. The increased draw lowered water tables and soon these wells also ran dry. Without water, crops and livestock suffered. By 2011, over 75% of farmers reported total crop failure. Livestock numbers dropped by 85%.

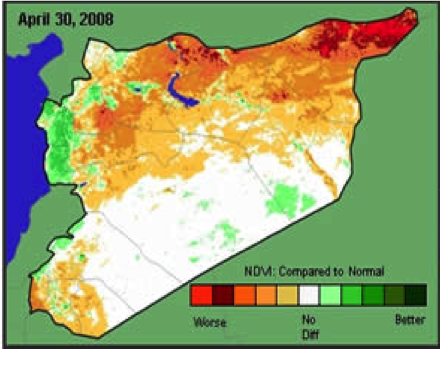

The worst drought in recent history

The latest drought was the driest period on record and the winter of 2007-2008 the driest winter. But this only tells part of the story. In fact, historical records indicate that the frequency of drought in Syria is increasing. For example, three of the four most severe droughts have occurred within the last 25 years.

It is also getting hotter. Since 1900, the average temperature in the region has warmed by 2°F. Hotter temperatures dry out the soil, leaving little initial moisture when drought conditions form. Studies have suggested that the effects of the 2005-2010 drought were intensified because the environment did not have time to recover from the previous one.

Moving to the city

With no jobs and facing the threat of starvation, rural farmers and their families migrated to cities. 1.5 million people moved into towns that only a few years earlier saw an influx of over 1.3 million Iraqis fleeing war. Urban populations grew by over 50% in less than 10 years.

The relocated farmers and their families competed with long-standing urban dwellers and refugees for low-paying jobs. Unemployment rates skyrocketed, and a lack of food drove prices to unaffordable levels. By 2011, 3 million of the country’s 10 million inhabitants were facing food shortages.

State officials offered little in the way of support. Less than 30% of a promised $43 million in state aid made it to the cities. International support was restricted to the drought-stricken regions. This provided aid for the few remaining farmers, but nothing to the farmers and their families struggling to live in Syria’s urban centers.

The ensuing civil war and the role of climate change

Protests arose as a result of perceived government inaction. Government officials pushed back to quell the protests. The resulting civil war has killed over 200,000 and has affected half of Syria’s population.

So, while recent studies cannot directly link climate change to conflict, the study by Kelley suggests that the changing environment, under the right socio-economic conditions, can drive a population toward conflict.

This is an important conclusion. As the effects of climate change continue to worsen, impacts will be felt by more and more people. If governments cannot adapt to these changes and develop resiliency plans beneficial to those affected, the threat of conflict will grow and spread throughout different parts of the globe.