Written by Drew Thompson (Assistant Professor of Historical and Africana Studies)

This past summer in June 2014, I traveled to Japan on the LIASE trip. As an African historian my research has involved particular geographical networks, Mozambique, Portugal (the former colonizing power of Mozambique), and South Africa (with its own history with apartheid and regional colonization). Mozambique has a longstanding history with the continent of Asia, which the recent rush to extract mineral resources in Africa and a wider global debate on China in Africa has brought into the foreground. My interest in traveling to Japan extended from a curricular and research standpoint. First, the Japanese government maintains both an embassy and international development corporation in Mozambique. Second, Japan and Mozambique share similar historical trajectories, histories of political dictatorship and democracy and confrontations with natural disasters. Also, in my own research about the role of photography in Mozambique’s independence from Portugal, I learned that a Japanese photographer visited northern Mozambique in the 1970s, at time when the liberation group Frelimo was at war with Portugal. In terms of academic curriculum, China’s engagement with Africa has been central to African history, and the disciplinary field of Africana Studies, and it is more important than ever to consider ways of incorporating studies related to Asia and Africa-Asia exchange within the field of Africana Studies. This urgency has also lead me to wonder why such histories of exchange remain absent from historical narratives in Africa (but definitely not absent from popular memories), and whether nationalist governments in Sub-Saharan Africa have played a role in controlling the ways in which the histories of Asia-Africa exchange are told. What are the political and analytical stakes of exploring and telling histories of Asia-Africa exchange at the present moment?

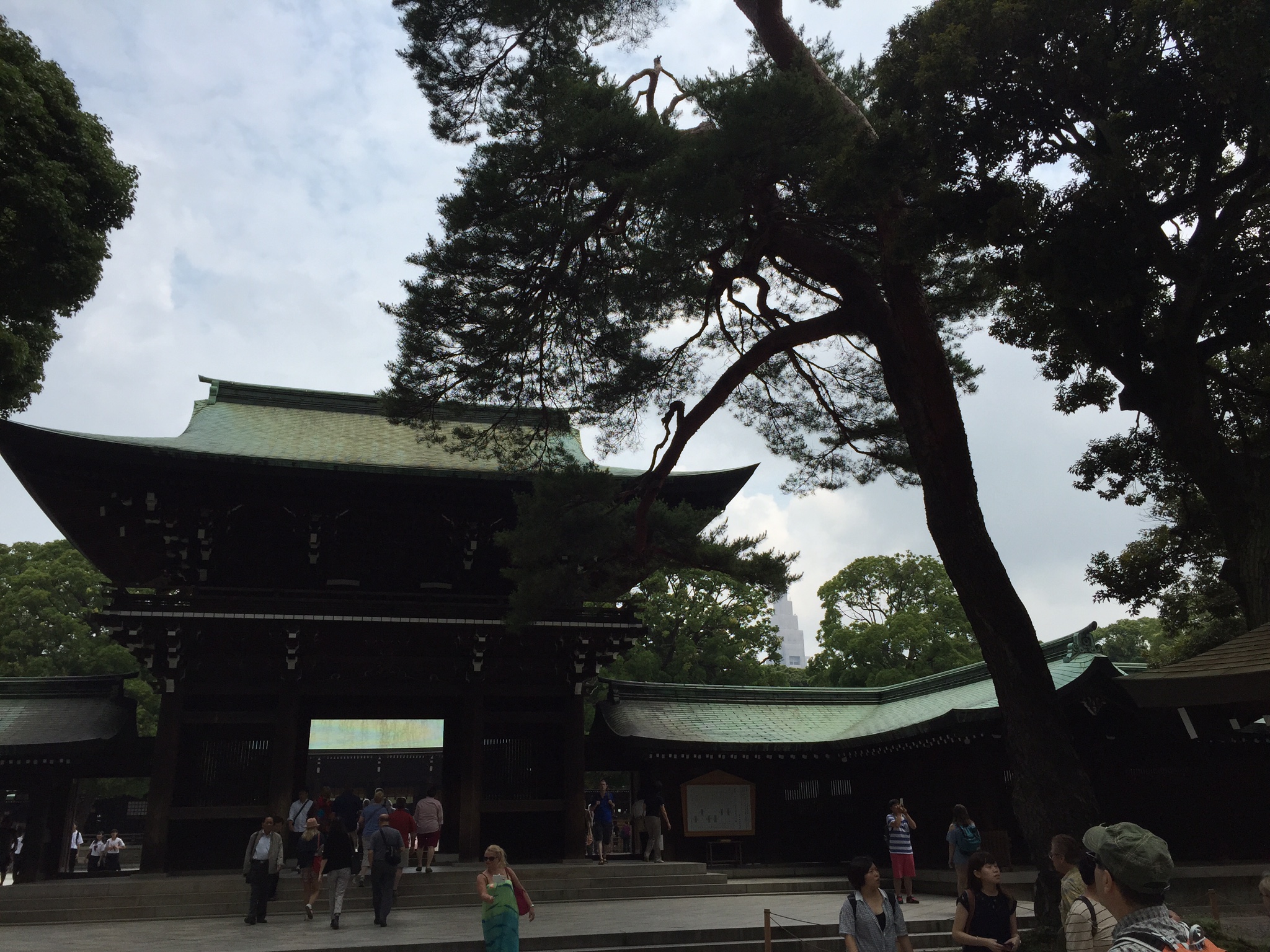

I was immediately both overwhelmed and intellectually stimulated upon arrival in Japan. There was an instantaneous language barrier, resulting in my reliance on language translators to navigate the urban and rural landscapes we traveled. What also struck me most was the scale of cities, the concentration of people in small spaces and the rich cultural practices, that range from visiting temples to riding subways in almost complete silence, that people deploy in their daily lives. The LIASE trip experience brought into particular juxtaposition for me the wide-ranging economic and technological innovations that characterize daily life Japan and the resiliency that allows for, and often follows after, disaster response.

One experience that stands out is the group’s visit to Ishinomaki, where we viewed firsthand ongoing efforts to rebuild after the devastating 2011 tsunami. Local guides invited us to trace the days events that lead up to and followed after the 2011 tsunami. By listening to stories (re-)lived by residents and walking through disaster affected areas, we also observed the challenges to rebuilding after a tsunami. I was particularly moved by the ways in which infrastructure, here understood as housing projects and roads, captured, preserved, and performed the historical memories associated with the tsunami disaster. The simple act of walking outside a front door or walking down a street had the potential to immerse residents in complex sets of dilemmas and historical experiences. What I also saw firsthand was the ways in which the Japanese government through construction companies, equipment, and contract processes activated a type of disaster response that is not visible on the African continent. This observation also drew into relief for me new ways about thinking about the spatial and architectural relics that remain on the African continent after foreign and regional colonization. The other aspect of the trip that was of interest to me was how tourism, activism, and artistic production are intertwined and unfolding in a place like Naoshima with the construction and operation of the Benesse House and Benesse Art Site. During this visit to Naoshima and the surrounding islands, we encountered copper refineries next to art installations by leading artists. There was a sense, from my perspective, of the co-existence and inter-dependencies of environmental degradation, histories of disaster, art exhibition, and cultural memory.

Since visiting Japan, the LIASE trip has had important impacts on my teaching of the urban histories of Lagos, Johannesburg, and Nairobi and the activities of the Africana Studies concentration here at Bard. First, I often use my experience in Japan to instruct students to be more attentive to the cultural practices that mediate their experiences moving through urban and rural spaces. For example, referring to the building and use of the Shinkansen has been helpful to student understandings of the impacts of the building of the railroad on a city like Nairobi. Also, Africana Studies recently hosted the journalist and scholar Howard French, who traced a history of China’s engagement with Africa and helped students to think about China’s political, economic, and social impact on Africa and the ways in such contact on the continent impacts daily life in China. With the trip to Japan, new teaching, research, and professional opportunities have developed for me here at Bard.