Last fall, I attended the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21), where I met Joyce Coffee, a self-described “Midwest-based adaptation maven” and an advocate for corporate sustainability solutions. I recently reconnected with Joyce to discuss the role of adaptation in global climate leadership and how governments, nonprofits and businesses are innovating for adaptation.

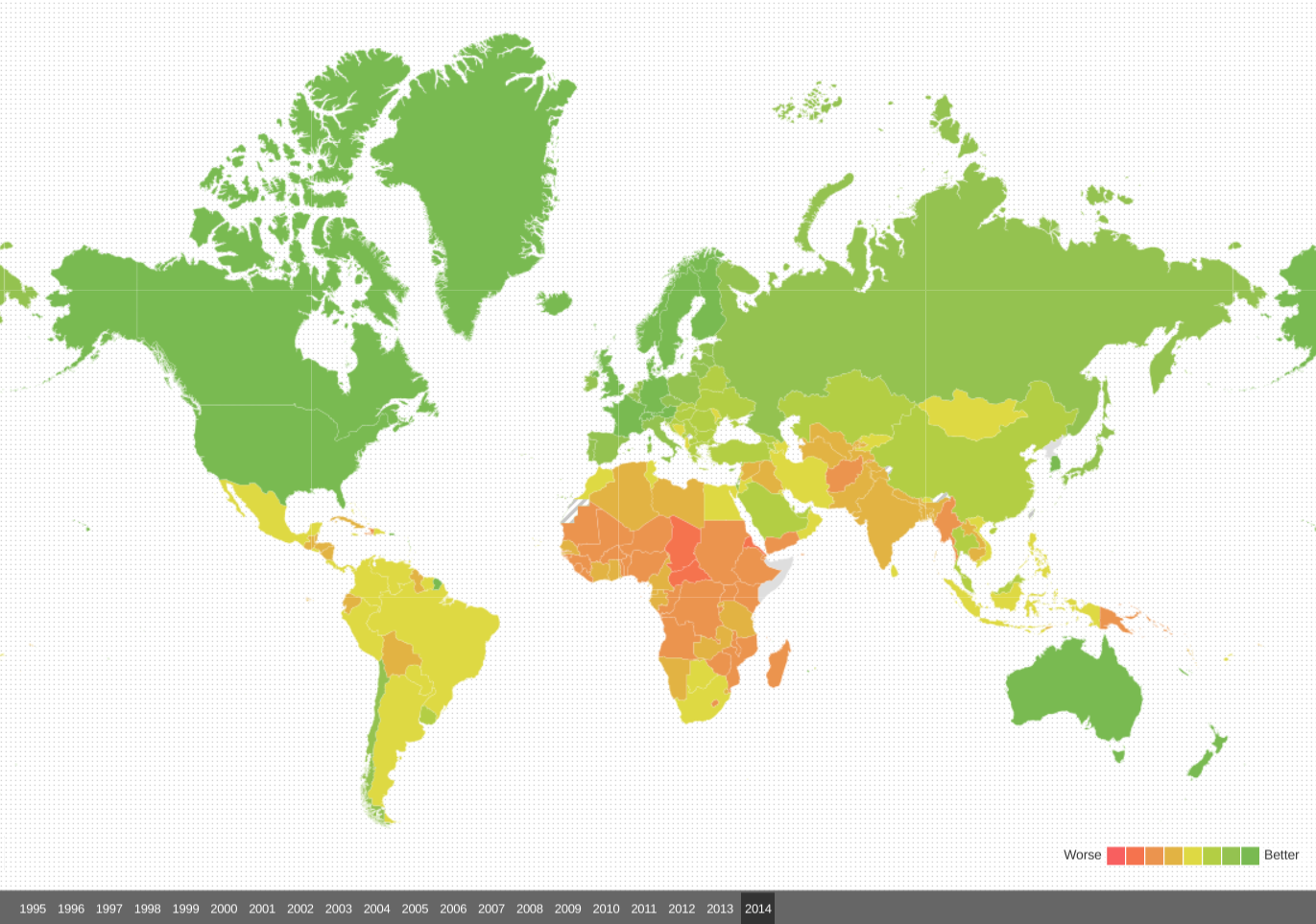

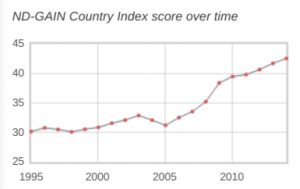

Joyce Coffee is the Managing Director at the University of Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index (ND-GAIN), a research institute that provides insights to inform public and private actions on climate adaptation. By identifying challenges and opportunities in climate adaptation, the ND-GAIN helps stakeholders make efficient investments towards adaptation in the water, health, food, infrastructure, security, and governance sectors. Its flagship product is the Country Index, a snapshot of climate adaptation challenges and opportunities with 15 years of data from over 175 countries. In addition to measuring vulnerability, the Index also evaluates how ready countries are to implement adaptation solutions that tackle overcrowding and resource constraints brought about by climate change. This two-pronged strategy is particularly useful for illustrating how institutions and social systems can modify a country’s capacity to deal with climate disruptions and drive changes in comparative resilience.

Joyce Coffee is the Managing Director at the University of Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index (ND-GAIN), a research institute that provides insights to inform public and private actions on climate adaptation. By identifying challenges and opportunities in climate adaptation, the ND-GAIN helps stakeholders make efficient investments towards adaptation in the water, health, food, infrastructure, security, and governance sectors. Its flagship product is the Country Index, a snapshot of climate adaptation challenges and opportunities with 15 years of data from over 175 countries. In addition to measuring vulnerability, the Index also evaluates how ready countries are to implement adaptation solutions that tackle overcrowding and resource constraints brought about by climate change. This two-pronged strategy is particularly useful for illustrating how institutions and social systems can modify a country’s capacity to deal with climate disruptions and drive changes in comparative resilience.

At ND-GAIN, Joyce leads a team of academics, policy analysts and consultants, engaging with the private sector, policymakers and non-governmental community to advance the impact of the Country Index and other adaptation-related research. She has extensive experience building coalitions between corporations, citizens and government agencies in her previous roles as the director of the Chicago Climate Action Plan (CCAP) and Vice President, Business and Social Responsibility at Edelman. She also runs the Climate Adaptation Exchange blog.

Not all corporations are bad

In our conversation, Joyce explained that thought leadership on adaptation initiatives and innovation in supply chains can engineer more sustainable outcomes even as climate change and extreme events disrupt water access and agricultural yields. Therefore, expanding access to and more sophisticated use of information through tools like the ND-GAIN Country Index will play an increasingly important role in building climate resilience. Since the Index is free and open-source, it has the potential to create an ecosystem of climate adaptation leaders through its country-level rankings and analyses as it offers guidance for decision-makers to incorporate climate adaptation within their strategic policies.

Notwithstanding its complex functions, the Index itself is simple and elegant. This feature piqued my interest about its deployment in the field. According to Joyce, the most prolific users of the Country Index are large financial and development institutions such as the World Bank, the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and USAID, which deploy its vulnerability and readiness indicators to guide programming objectives and allocate funds. ND-GAIN also targets infrastructure contractors and large landowners. This is because construction and engineering firms will need to mitigate the physical impact of extreme weather events and sea level rise on utilities and new infrastructure. Meanwhile, the food and beverage industry also represents another important user group for ND-GAIN products due to its dependence on agricultural commodities and other natural resources. Changing growing conditions, including droughts and unexpected precipitation, will modify the fecundity of cash crops like coffee, cocoa and vanilla. Already, conglomerates like Mars Inc. and Pepsi Co. are leveraging adaptation investments to reduce business risk from climate-related hazards and natural disasters in the countries in which they operate.

Government innovation in adaptation to extreme events

Countries can also utilize adaptation insights to integrate climate change considerations into economic forecasting and policy formulation. ND-GAIN recently assessed infrastructure vulnerability across the United States, Mexico and Canada, finding that while the US has the highest infrastructure vulnerability score it is the least vulnerable to sea level rise impacts compared to the other two countries. Joyce remarked that although the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act (SRIA) of 2013 made no mention of either “climate” or “adaptation,” it is effectively a piece of climate adaptation legislation. This is because of its focus on hazard mitigation and the resultant adoption of stricter building and siting standards for housing and other infrastructure. With increased visibility on aging infrastructure from natural disasters like Hurricane Sandy, targeted funding towards adaptation measures, explicit or otherwise, will prevent future damages and therefore reduce future disaster recovery costs.

Joyce also noted that extreme events are teachable moments for how local government policies can foster readiness strategies and lead on climate adaptation issues. She cited the 1995 Chicago heat wave as a classic failure to adapt. Record temperatures and high humidity in the summer of 1995 caused over 700 deaths in the Chicago area. As power use spiked, electric utilities in Chicago and other cities across the Midwest were overwhelmed by the demand for air conditioning, leading to power shortages. Insufficient ambulance service and hospital facilities, lack of preparedness and inadequate warnings from city officials exacerbated the impact of the heatwave. The group most affected by the heat wave was elderly and poor residents who could not afford air conditioning and who were afraid to open their doors and windows due to their fear of crime.

To tackle extreme events like the 1995 heat wave and deal with climate change more broadly, the City of Chicago adopted its Climate Action Plan in 2008. In addition to funding research on the urban heat island effect, the plan includes an extensive heat wave response effort, focusing on vulnerable populations, as well as strategies to encourage greenscaping and the installation of reflective roofs.

The role of socio-cultural factors in climate adaptation

Although corporate climate actions and local government policies have enormous power to facilitate adaptive strategies, social and cultural factors, which are more difficult to define and measure, can also drive readiness and community responses to extreme events. To illustrate, Joyce brought up the resilience of Vietnamese-American community in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina to illustrate the impact of social systems for adaptation. Many researchers have attributed the robust recovery of this community, in comparison to other ethnic or racial groups groups, to its sense of collective perseverance drawn from common religious and socio-political perspectives within the group.

Likewise, according to the Country Index, Rwanda has seen the largest gains in readiness compared to any other nation. This is partly due to its experience of strife immediately prior to the start of data collection for the Index in 1995. However, its political stability, the effective rule of law, combined with reduced social inequality and the rise of new information economies, have driven its recovery. These socio-cultural indicators are hard to ignore and decision-makers, including the private sector, must recognize the opportunities to invest in climate adaptation within this framework of social readiness. Joyce stressed that adaptation is all about innovation, in both infrastructural, physical sense and but also in social structures and behavior change.

Scaling leadership on adaptation

Adaptation issues featured prominently during the COP21 negotiations, and the resulting Paris Agreement notably defines a long-term adaptation goal. Prior to COP21, adaptation commitments were often included as an afterthought to climate mitigation plans. However, the COP21 agreement aims to accelerate adaptation responses by mandating a schedule for national adaptation communications in order to take stock of progress on achieving this goal. The agreement also includes a call to balance climate finance between adaptation and mitigation.

Notwithstanding these commitments, Joyce suggested that it will be important to set baselines for climate finance for adaptation and and make it more relevant to stakeholders outside the climate governance and and sustainable development spheres. This would encourage climate leadership in adaptation at all levels and ND-GAIN is currently developing a theory of adaptation measurement at the urban scale. She envisions the Country Index evolving from a score into a qualitative rubric that empowers stakeholders to build capacity to make adaptation plans and implement these strategies. Perhaps, a global adaptation standard may even be on the horizon.