Imagine the protein content in foods you eat every day decreasing. Foods that are staples around the world–wheat, corn, rice–all lower in protein and higher in carbohydrates. Science has already shown that global crop yields will decrease in coming years because they won’t be able to take the heat. But a recent article in Nature has now shown that these crops will also be less healthy.

Where are we now?

People around the world, especially in developing countries, rely on staple crops like wheat, corn, soybeans, and rice for nutrition. Iron, zinc, and protein are especially important for human health. These staple crops aren’t high in iron or zinc, but in the developing world, they’re still a main source of these nutrients. Over 2.4 billion people get most of their iron and zinc from these staples.

Where will we be in 50 years?

These are exactly the nutrients that are expected to suffer under climate change. The increase CO2 in the atmosphere has been shown to decrease the amounts of iron, zinc, and protein in these important staples.

The Nature study shows that crops could have as much as 10% less of these important nutrients. So where does this leave food insecure people? Many already suffer malnutrition, and these people will have to get 10% more food to get even the bare minimum in minerals and protein that they’re getting now.

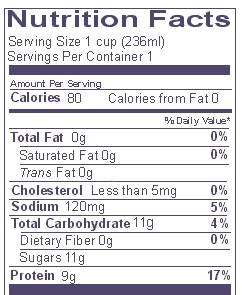

We already need to nearly double food production by 2050 to meet growing population needs. Even if we manage to grow enough for 9 billion people to eat 10% more than we eat now, it’s not a solution. 10% more food means 10% more calories, and those calories are mostly carbohydrates.

Health Concerns

We’re facing malnutrition if we eat the same amount and too many carbohydrates if we eat more. Both options can lead to a wide array of health concerns, including:

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Heart disease

- Stroke

These last three are metabolic syndromes already common in the developed world and associated with obesity. But Samuel Myers, lead author of the study, says that the shift to higher carbohydrate foods can cause these diseases in the developing world even without the overeating we see in the developed world.

Are GMOs our only hope?

Can we breed crops that will solve the problem? Many GMO proponents believe that genetically modified crops will be the best way to deal with high CO2 reducing nutritional value. There are two ways to approach breeding: breed for resistance to high CO2, or breed for crops with higher nutrients.

The first option, breeding for higher CO2 resistance, can be done with traditional breeding methods rather than GMOs. Some of the staple crops are already more resistant than others: for example, corn is a C4 crop, a type less vulnerable to CO2, and soybeans are a legume, so they don’t experience the same decrease in protein as the others.

However, Myers believes that breeding for CO2 resistance won’t solve the problem. Farmers choose which seeds to use, and many factors are prioritized above CO2 resistance, including:

- Price of seeds

- Yields

- Disease resistance

- Pest resistance

- Ability to withstand drought

- Taste

The second option, creating crops with higher nutritional value, has been attempted with GMOs. A famous example is the golden rice project, which created a type of GMO rice enriched with vitamin A. However, there currently aren’t any nutrient-enriched GMOs that are approved for human consumption, and people are unlikely to completely replace a product that has been historically a staple with an untested new variety.

Solutions

As is the case with many of the problems that climate change presents, this issue is complicated with no obvious solutions. Even if we could grow more, eating more isn’t the answer, and GMO improved nutrition crops have been highly controversial. This controversy leaves doubt that they will be implemented on a wide enough scale to make a difference, if they are implemented at all.

However, we may be able to make more progress focusing on the root problem rather than the symptom. Instead of dividing resources to address problems from crop nutrition to coral bleaching to climate refugees, we could work on all of these problems simultaneously by putting our resources toward curtailing emissions and reducing the magnitude of global climate change. We’re already locked in to some of the changes, but a focused effort could mitigate some of the worst effects. This study provides yet another reason to address the greater problem.