Continued from Part I – New England Forests

“A leader is best when people barely know he exists, when his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say: we did it ourselves.” —Lao Tzu

Highstead

New England’s grassroots conservation organizations continue to innovate around individual challenges. Those that successfully span boundaries to form partnerships are helping the land trust movement adapt in the face of uncertainty. These thought leaders are showing us that conservation, as a whole, really can be greater than the sum of its parts.

Such is the case at Highstead, a small conservation group in Redding, CT with a big impact across New England. In partnership with the Harvard Forest and Harvard University, Highstead leads the Wildlands & Woodlands (W&W) vision, collaborating on initiatives such as the Regional Conservation Partnership (RCP) network and the New England Forest Policy Group.

W&W has ambitious goals to keep 70% of New England’s forests free from development, support a land-based economy, and provide environmental and social benefits for generations to come. W&W is also set to release a renewed vision later this year, one that will fully integrate protection of forests, farms, clean water, and sustainable land-based livelihoods, while calling for stronger connections between our cities and rural areas.

Leadership Through Collaboration

I had the pleasure of speaking with Spencer Meyer, one of Highstead’s Senior Conservationists, about how he and the other staff at Highstead approach leadership.

“We are a quiet leader,” said Meyer. “Our niche is in convening conservation partners, to showcase their work in the context of a bigger picture, and to inspire them to advance the collective conservation mission. We convene people with policy, conservation finance, and on-the-ground conservation expertise with landowners to find ways to do more through partnerships.”

In fact, Meyer says his career has always been about being an “honest broker” between groups of people. For example, at the University of Maine, Meyer led an interdisciplinary team of economists, ecologists, natural resource managers, lawyers, and GIS mapping specialists to develop the Maine Futures Community Mapper. This tool allows local decision makers to address conflict areas upfront and strategically plan for least-conflict areas in the future.

Meyer noted, “It takes a lot of time to engage people all throughout a [collaborative] project, but you come up with a better, more relevant product in the end. We learn a lot from bringing people together.”

Meyer is also seeking to collaborate across international borders. He recently attended a conservation finance workshop in Chile organized by the International Land Conservation Network. He noted that similar themes exist across borders even when land-use rights vary. To accelerate conservation and make it more effective, he says we need three things: the legal framework, the right incentives for landowners, and more resources in the system to make conservation go further.

Meyer is also seeking to collaborate across international borders. He recently attended a conservation finance workshop in Chile organized by the International Land Conservation Network. He noted that similar themes exist across borders even when land-use rights vary. To accelerate conservation and make it more effective, he says we need three things: the legal framework, the right incentives for landowners, and more resources in the system to make conservation go further.

Back at home in New England, Meyer and his Highstead colleagues recently convened regional and national experts on conservation finance to brainstorm new strategies for increasing public and private investments in conservation. He and his partners are looking toward environmental markets, private investments, and policy that builds on strong public support for land conservation to leverage even greater funds for conservation.

A New Forest Legacy

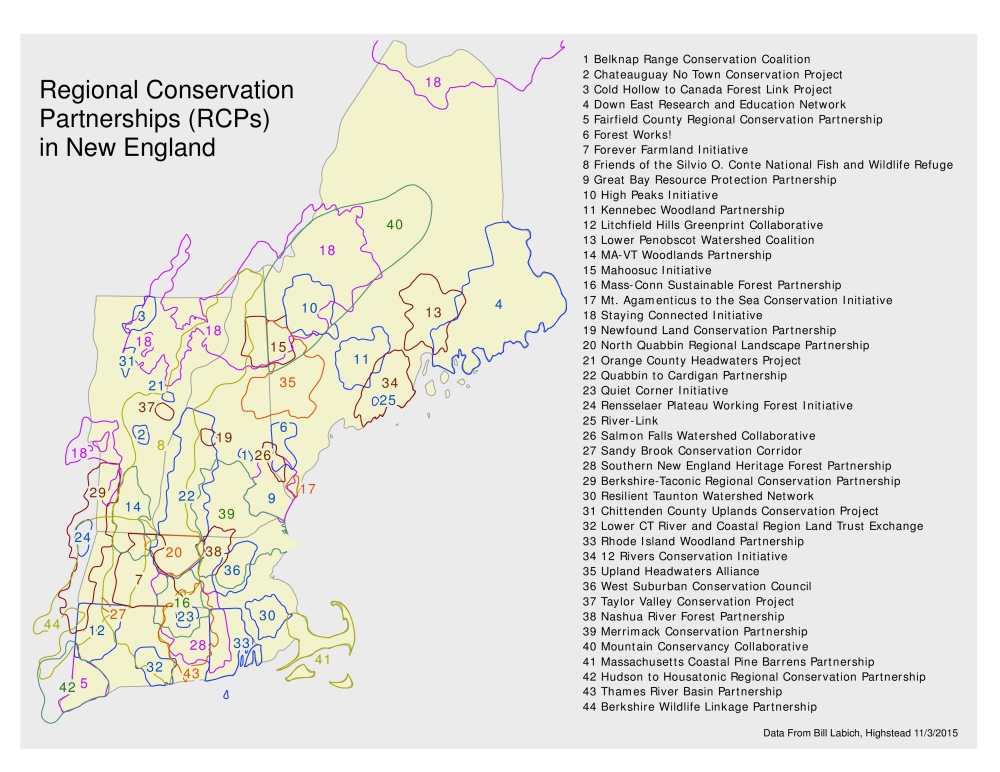

The reach of Highstead’s collaboration is extensive. From Connecticut to Maine there are 43 RCPs working in areas spanning 55% of the region’s natural landscape. Highstead helps bring the RCPs into closer interaction with one another at an annual gathering.

“Bill Labich is our conservation partnership guru,” said Meyer. “He has really spearheaded the RCP Network and wrote the handbook for forming effective regional conservation partnerships. These RCPs are helping shape the future New England landscape through the remarkable work of all the individual landowners and organizations working together.”

I asked Meyer how he came to find himself working in such a dynamic space with connections to many people. He said, “Growing up I was always looking to spend time outdoors and had a deep curiosity about the world around me. So all along I’ve been a people-person and want to know what people’s interests are and how they connect to the natural world.”

“That’s what conservation is really about. We are trying to understand what other people’s appreciation of the land is and help steward it. Working in the spaces between agendas and between organizations is where I’ve felt most at home, and I’ve found it’s also an effective place to be.”

Current conservation organizations are thus creating another kind of legacy to weave into the New England landscape: one in which the cumulative effort of men and women who care for the land and the livelihoods it provides helps ensure that healthy forests remain in New England forever.

Perhaps one crisp fall day many years from now, a teenager will take a walk through a protected forest and recognize a different legacy than the one we see today in stone walls. Perhaps he or she will see the results wrought by the dedication and collaboration of today’s conservation leaders.