I also experienced the extensive nature of new environmental policies firsthand in my research for the NYC Council’s EP Committee, where the bulk of my efforts focused on finding creative policy ideas to solve current water issues, particularly stormwater.

Stormwater challenges in NYC

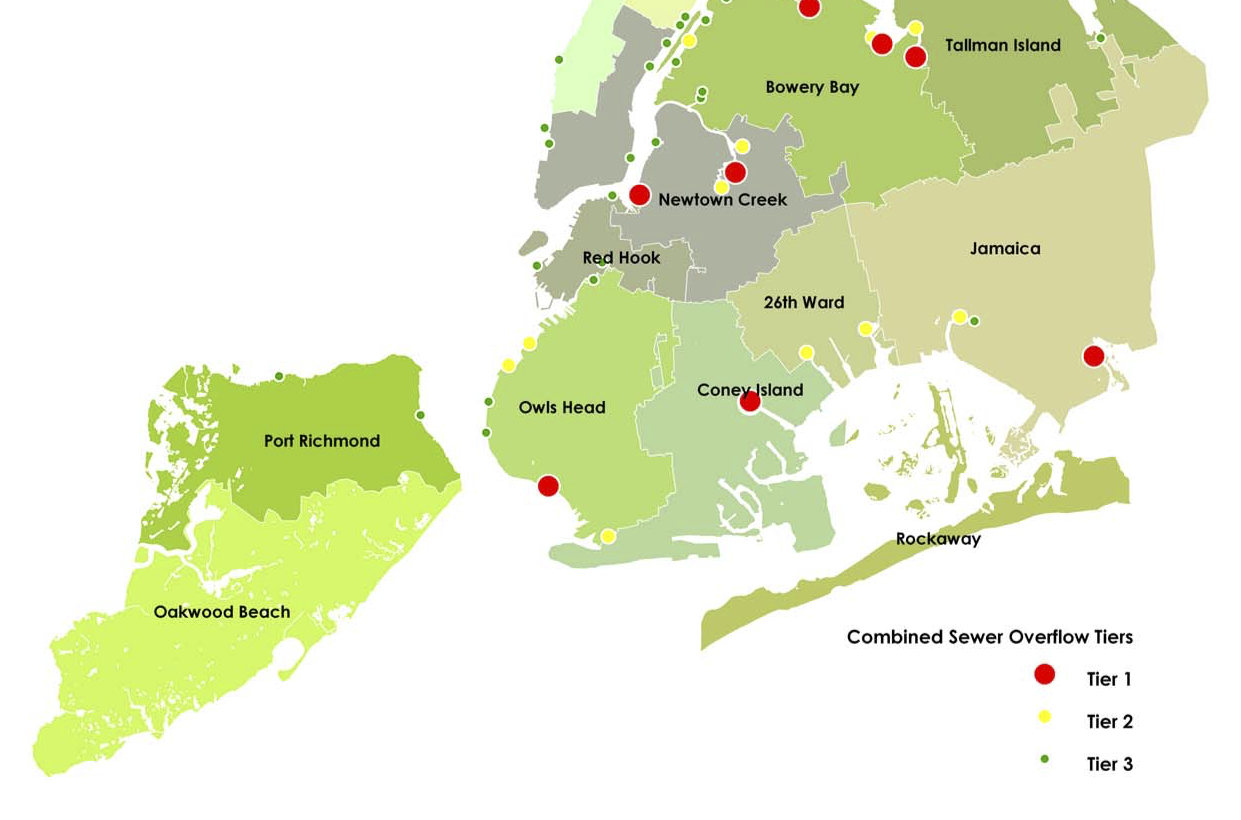

New York City, like many other cities, experiences ongoing stormwater issues, originating in large part from combined sewer overflows (CSOs). CSOs occur during heavy rain events when stormwater runoff and untreated wastewater inundate the sewers and wastewater treatment plants, spilling excess water directly into city water bodies.

Source: [thecityoftoronto]. (2017, August 21). What is a combined sewer overflow (CSO) [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ev64xXDYmaw

As a result of the ongoing CSO events, New York State’s Department of Environmental Conservation and the NYC DEP signed an agreement in 2012 in which the DEP committed to develop long term control plans (LTCPs) to treat the sewage overflow and improve water quality city-wide in compliance with the Federal Clean Water Act.

What new policies at the city level can help reduce stormwater volume?

In order to first get the lay of the land, I waded through different policy documents, financial reports, and sustainability roadmaps published by the DEP, the Mayor’s Office of Sustainability, and the NYC Water Board. I familiarized myself with Legistar, which stores records of all legislation proposed and/or passed by NYC Council members. Then, once I felt comfortable with existing policies, I looked up case studies of other successful urban stormwater policies as well as peer reviewed literature on stormwater innovations.

After a year at Bard CEP, I understand that water issues, much like energy or waste issues, require systems thinking, where different policies can solve a problem from various angles. In this case, to reduce outputs like stormwater and wastewater (i.e. toilets, sinks, laundry, showers), I examined inputs to the system (i.e. rainwater and municipal fresh water) as well as any potential feedback loops (i.e. water recycling or re-use).

Ultimately, I concentrated on the potential of using filtered rainwater and/or recycled water in NYC to reduce rainwater inputs and wastewater outputs to prevent CSO events.

Here are some of the questions I grappled with:

- Is there potential to reduce input and output especially during storm events by facilitating rainwater capture and re-use as well as water recycling within a building?

- Does NYC have rainwater re-use and water recycling policies in place? If not, what are the barriers? How can NYC incentivize these policies?

- What do rainwater re-use or water recycling policies look like in other cities? Which have been successful and why?

What makes NYC a unique case study?

In many cities, the solution for stormwater events has been to incentivize wastewater efficiencies and stormwater reduction through stormwater fees and demand management, where installed water meters capture the flow of water and charge based on that data. Residents can then reduce water rates through on-site efficiencies like low-flow faucets and water re-use systems, and they can also lower stormwater fees through on-site green infrastructure like permeable pavement, green roofs, and rain gardens.

NYC presents a unique case because its Water Board, whose members are appointed to two-year terms by the Mayor, set the water rates annually. As policymakers at the New York City Council have no power to change water rates, I had to approach new policy ideas to reduce stormwater from other angles. Urban Green Council’s Green Codes Task Forces has been particularly helpful to identify roadblocks in existing laws and codes to the use of filtered rainwater and recycled water in buildings or homes.

I hope some of my ideas can re-spark a conversation about the potential of rainwater re-use and on-site water recycling in the larger context of NYC’s efforts to reduce water demand by 2021.